AWS for Industry, But Better: The Railroad Investment Case

If you're choosing where to work, you probably want to aim for secular growth. A growing industry has growing headcount, increasing responsibilities, and improving economies of scale, and that's good for career prospects whether you want to rise up the ranks as a manager or work as a specialized individual contributor. In a shrinking industry, you suffer the tyranny of the long generation, where organizations get more risk-averse as the median employee ages, and start to promote more based on seniority at exactly the time when the people who already work there are accumulating a lot of it.

For investors, the picture is more complicated. A growing industry can make fortunes, and the biggest net worths all tend to derive from growth. But growing industries have much more competition, and any time available capital is increasing faster than the opportunity set, expected returns will decline. Railroads are, in relative terms at least, the most non-growth industry imaginable, since they used to be most of the market and went through a roughly century-long decline featuring massive losses, painful consolidation, and the largest bankruptcy in history up to that point from the Penn Central.1 This decline had several causes:

- Passenger rail was an important revenue source early in railroads' existence, but total passengers peaked in 1920 and had declined by more than half by the 50s thanks to the rise of the automobile. Rail-based passenger transportation can work in some contexts, like dense cities (the MTA carried 5.5m riders each weekday in 2019, above the entire US rail system's passenger traffic at its peak, but short hauls have different economics than longer ones, and the MTA still needs heavy subsidies).

- Trucking devoured market share in freight transportation in the mid-twentieth century. The Interstate Highway System was a big factor here, and in the decade after, trucks took 7 points of freight share from railroads, becoming the biggest single category of freight.

- Railroads benefit when more supply chains are domestic, and containerization made it easier for low value-added parts of the manufacturing process to move overseas. A US-manufactured car might need trainloads of steel, and that steel mill would require trainloads of iron and coal. When segments of the supply chain move overseas, that has a disproportionate impact on the railroads, which earn revenue from every step that happens over land instead.

- Railroads were especially well-adapted to bulk transportation. As they lost share in other kinds of transportation, they remained dominant for coal, but coal has been in terminal decline since 2008.

- Unit economics for railroads look best when each locomotive is pulling lots of cars. Railroads that wanted to optimize their unit profitability traded-off on scheduling: if one customer was a day behind for a big shipment, they'd wait, but that meant that the next customer would be behind, too. (The popularity of just-in-time manufacturing is not compatible with a delivery date where the error bar is 20% on either side.) And those scheduling problems interacted badly with a heavily-unionized workforce which had lots of rules around work hours. If a shipment was a few hours late, it might arrive after the end of the last shift instead of in the middle of it, which would require the railroad to bring in a new crew (having already paid the previous one to wait).

- As a legacy of the industry's growth, there were many cases where multiple companies could service the same routes. As their total volume declined, they competed more on price; the fixed costs would exist regardless of how much they carried, so it was better to turn a tiny incremental profit than to have idle tracks, equipment, and workers.

- Because of all these negative trends, smart managers generally avoided the industry. This compounds problems. An industry won't be adaptable when most workers are trying to hang on long enough to collect their pensions, and it won't take many risks when change has only had downsides for decades.

So every secular trend possible has been conspiring against the train industry for an astonishingly long time. That's one side of the ledger. The other side is that the US has the best freight rail infrastructure in the world, and rail transportation is about 80% cheaper than trucking per ton-mile. And trains and trucks can be combined to achieve rail's cost savings for one part of the route and trucking's flexibility for the rest.2 If the industry got its act together, that cost advantage and irreplaceable route network could produce some good returns for investors.

The industry did, in fact, get its act together, and attracted interest from smart investors. Warren Buffett bought BNSF in 2008, Pershing Square won a tough proxy fight with Canadian Pacific in 2012, which turned into one of his most successful investments ever by 2016, and this interview with Eric Mandelblatt at Soroban is a good overview of the current bull case on railroads. (The Soroban interview gets credit for putting this industry back on my radar. I've actually spent a lot of time thinking about railroad economics due to a high school addiction to Railroad Tycoon II, but hadn't looked seriously at the industry until recently.3)

The story of how that happened is partly about a bad situation that ran out of ways to get worse, and partly a story about how the assets these companies have were valuable all along. Part of the bear case on railroads is environmental; coal is still a big chunk of revenue, and derailments that spill oil can be incredibly dangerous. But the bull case, too, is an environmental one: drawing a line on a map, flattening it, and ramming steel into it at scale is just not something the US will really allow; all it takes is one recalcitrant landowner or one potentially-endangered species anywhere between point A and point B to nix the project. Railroads needed to find a way to fit in to a just-in-time environment, and they found it by rethinking their unit economics and leaning in to their cost advantage.

Why American Rail Infrastructure is Great

The economic model for railroads is not too far off that of big tech: there's a fixed asset that leads to a hard-to-match competitive advantage, and variance in outcomes is driven by how well companies exploit that asset. It might sound like a stretch to say that someone who likes investing in software businesses would also want to invest in a heavily unionized, smoke-emitting industry, but it's true: Cascade Investment Group, the family office for the Gates fortune, used some of the proceeds of its Microsoft sales to become the largest shareholder in Canadian National.

Understanding the railroads starts with understanding that asset base.

America in the present, is very fortunate to have been very sloppy and irresponsible in the distant past. The story of why the US has such a marvelous railroad network is one of over-optimism, bad math, market manipulation, and flagrant corruption. Railroads were about two thirds of the market in 1900, and other big chunks like banks, steel, and telegraphs were intimately tied to the railroad industry's fortunes. No industry has ever dominated the market so much, and no industry ever will again.4 Right now there are basically three publicly-traded railroads in the US, with a collective market cap of around $250bn, worth about as much as Coca-Cola. In 1900, they had a million employees, and total revenue that was three times Federal tax receipts. Today, they employ around 135,000 people, and total revenues for North American Class I railroads were $73bn in 2021. (Back to the soft drink comparisons, that's a bit smaller than PepsiCo's $79bn.)

There were a few big drivers for the 19th century growth of the North American railroad industry:

Early on, railroads had a cost advantage relative to other forms of transportation.

They were also capital-intensive enough that they had to raise money through capital markets rather than banks. This made them a good conduit for foreign direct investment in the US; a British investor might have been skeptical of making a loan to a small American company, but could buy American railroads' bonds or shares and know that a) there were American banks monitoring the situation for them, and b) there was a liquid secondary market.5

Railroads, especially transcontinental ones, were heavily subsidized through government loans and land grants. As generous as these subsidies were, the railroads found ways to extract more value from them: the Union Pacific's lawyers found a poorly-written clause in a subsidy law, allowing them to reinterpret their interest obligations from subsidized loans in a way that added $43m in subsidized interest to an intended $77m loan.

Meanwhile, railroads operating before the advent of modern accounting, not to mention modern data storage and analysis, had no idea what their unit economics looked like. They simply couldn't calculate the breakeven price for a particular load, or what the incremental return was from adding a branch somewhere.

This doesn't mean that there weren't reliable ways to make money from the railroad system. There were two popular ones:

- Directly skimming money from construction, by creating a captive construction company owned by railroad insiders and politicians that overcharged the railroad and then paid dividends to supporters.

- Insider speculation in land based on foreknowledge about what route the railroad chose.

Both of these were harmful to the railroads' owners, and didn't do anything for customers, either. But it did create a strong internal incentive for companies to build as much as possible. New track meant more subsidies, more land grants, more opportunities to skim money from construction, and a chance to make money flipping acreage wherever the route went.

Since railroad investors weren't fully aware of how much they were being ripped off, they tended to overestimate profits. Between speculation, subsidies, and theft, every possible incentive aligned to build as much track mileage as possible. Rail mileage peaked at over 250,000 miles in 1916, by which point the industry had already gone through several cycles of boom and bust (a quarter of the rail system by mileage was in bankruptcy by 1893).

Since then, there's been a long retrenchment; total railroad mileage is around 92,000 today, with the pace of decline leveling out in the last fifteen years or so.

Transcontinental railroads shaped the US economy and culture (and politics, leading to the abrogation of several treaties with tribes whose land was along routes railroads wanted). That's even more literally true in Canada, where British Columbia's inclusion in the country was conditioned on the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Whether this turned out to be strong evidence for the power of industrial policy or a great argument against the corporate welfare state depends in part on your discount rate: the railroads wasted a lot of money at the time, but also bootstrapped the US manufacturing base, created the world's biggest financial market, and created a dense network of cheap over-land transportation that's still in use.

The Railroads Today

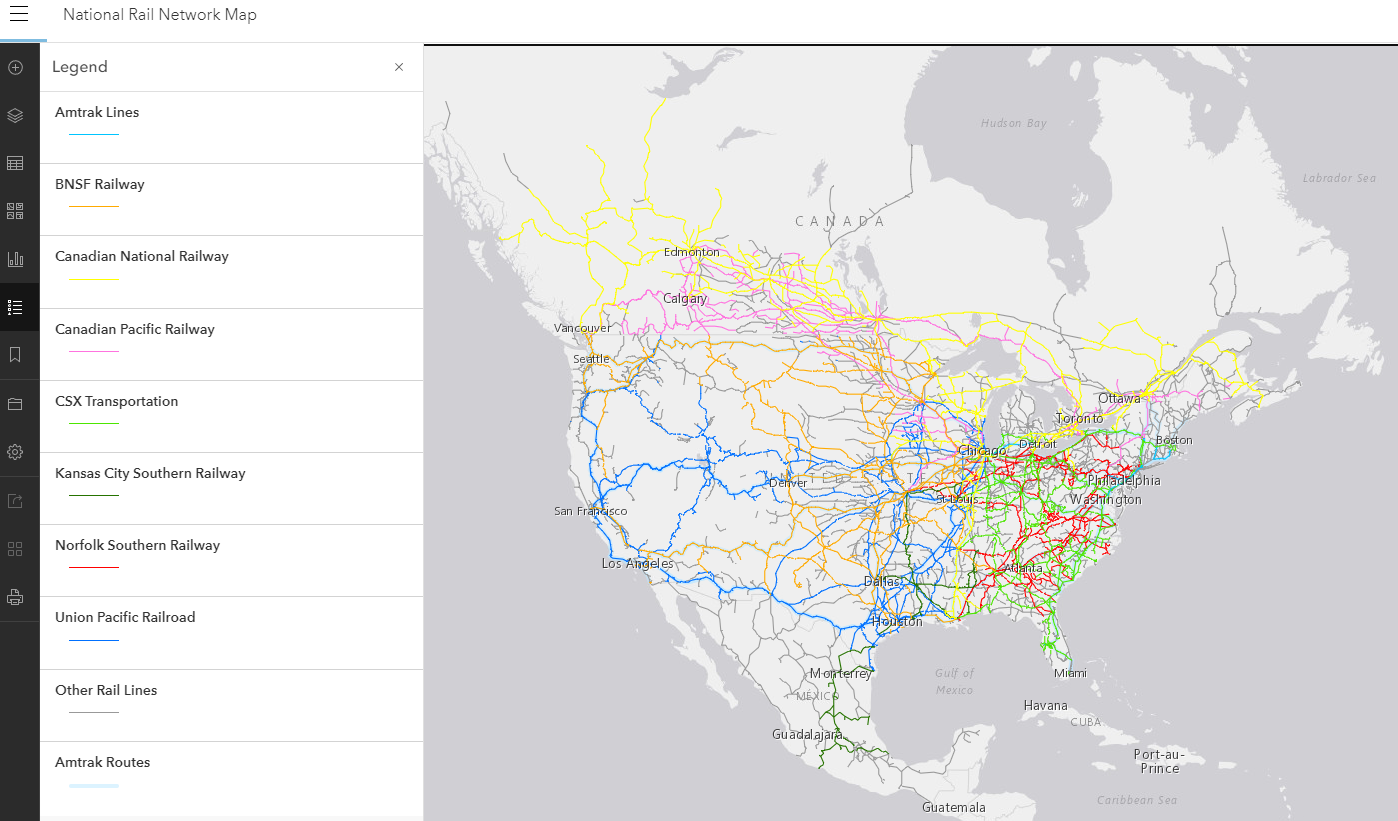

This map is a good look at where things stand today. There are railroads connecting every major port and population center. They no longer serve much of a purpose transporting people, but for goods the cost is hard to beat.

Whether that cost advantage accrues mostly to railroads' customers (and their customers' customers, i.e. American consumers) or to the railroad shareholders depends in part on how consolidated the industry is and on how it's managed. Consolidation was a long and painful process, and the management changes were, too.

It's always tricky to attribute industry-wide changes to specific individuals, but two stand out. One, a railroad executive, was the late Hunter Harrison, former CEO of the Illinois Central, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, and CSX. (He was a busy manager, and some of this job-hopping left serious bad blood on all sides.) The other was Harley Staggers, who sponsored a bill that deregulated railroads, allowing them to set whatever rates they wanted so long as there were competitors, allowing railroads to set up contracts with other shippers, and reducing each railroad's influence on other railroads' rates.

One reason Harrison was so effective was the Long Generation effect mentioned above: he joined the St. Louis & San Francisco in 1963, when the department he worked for had made just one or two hires since the end of the Second World War. Harrison was also an exemplar of working as an individual contributor well past the point where it's directly economically rational: at one point, as a CEO, he booked a hotel room with a view of a rail yard, spotted an idle train, and called the station to demand an explanation. Another time, again as CEO, he was working from home and noticed some congestion on his network status dashboard, called up the dispatcher of the relevant station, and then personally worked as a dispatcher for the entire night to clear things up.

This kind of obsession about detail is somewhat unreasonable, and could be quite expensive; Harrison was making tens of millions of dollars a year, so in terms of opportunity cost he spent around a dispatcher's annual salary by working as one for a single night. On the other hand, it has a nice multiplicative effect, especially if the CEO in question is better at negative feedback (e.g. screaming at people, firing them) than positive.

The more repeatable element of Harrison's impact was that he rethought railroad unit economics. Historically, what railroads aimed for was the longest possible train—every incremental car is cheaper, so if you measure P&L while trains are in motion, bigger is always better. But railroads are also a capital-intensive business; CSX's $13.1bn of annual revenue requires a $40.5bn asset base, and that asset base ignores the value of the long-since-depreciated-to-zero rights-of-way that make railroads so valuable in the first place.

If the sole priority is longer trains, something has to give—many things, in fact. Schedules, for example, will slip if a customer is late but could fill more cars given a day or two more. Idle equipment can proliferate, and trains can end up with suboptimal routes. And since customers have a sense of the railroad's economics, they know they can push prices down and demand more delays, too.

All this means that a railroad that doesn't adhere to a relentless fixed schedule is more capital-intensive than one that does. Harrison set out to fix this, with a focus on keeping schedule even if the customers weren't ready. This reduced idle time, and made the entire system more predictable. And since the customers who depended on rail transportation had a more flexible but much more expensive alternative in trucks, it basically gave those customers a continuous economic incentive to play along—helped by a) lower prices thanks to more efficiency, and b) a more reliable service, both because of scheduling and because a well-scheduled railroad will have fewer surprising mistakes.

Harrison's manifesto is actually available on Amazon (for $400), but this book is a good summary, albeit one highly favorable to the Harrison view of things. There are two strong datapoints in favor of Precision Scheduled Railroading. First, when Harrison agreed to join CSX it added $10bn to the company's market value in a few days; CSX was worth 28% more with Harrison as probable CEO than it had been before. And second, other railroads ended up adopting the same methodology; if you Google "precision scheduled railroading" today, the top result is from the blog of Union Pacific, which adopted it in 2018.

Railroads still face challenges. As of 2019, around 14% of their traffic still consisted of coal, which has been declining at around 6% each year. Overall railroad traffic is roughly flat over the last decade. But that means that traffic excluding coal has been rising in the low-single digits annually; as coal continues to decline, the broader secular trend towards more railroad shipping will push traffic up.

And that's just a general bet on economic growth. Where things get even more interesting is in looking at what happens if supply chains shift. Compared to the rest of the world, the US has expensive labor, cheap and flexible capital, fairly cheap energy, and expensive land. As manufacturing matures, it tends to get relatively more capital-intensive, possibly more energy-intensive, and less labor- and land-intensive. So one way to look at the broad global macro trend in manufacturing is that as the rest of the world gets richer, the US's comparative disadvantage in manufacturing starts to decline, because incremental manufacturing investment gets less and less sensitive to what's expensive in America and more and more tied to what's cheap.

This doesn't mean that we'll run the story of globalization in reverse, and that the US will once again be the world's dominant manufacturer; you generally don't want your country to be making lots of shoes, lawn furniture, and toys domestically, unless the alternative is subsistence farming or starvation. But it does mean that the cost advantage of offshoring some kinds of manufacturing gets weaker over time. That's especially true when long, distant supply chains get harder to trust, whether that's due to American foreign policy, Chinese foreign policy, or Chinese domestic policy; the US is just not capable of the sorts of drastic Covid lockdowns that the Chinese Communist Party has been able to enforce, so the US manufacturing base is harder for the local government to disrupt.

Because of their cost advantage in intra-US transportation, and because of monopolistic economics that are politically and technologically infeasible for anyone else to duplicate, the railroad industry represents a sort of royalty on the growth rate of domestic manufacturing (and, to a lesser extent, consumption of bulky products like cars, lumber for houses, grain for food, oil, etc.). A bit like the economic role cloud computing plays in the growth of software, or ads in consumption, higher spending on the end product leads to higher spending and better margins on the hard-to-replace intermediate.

One thought experiment to use on the railroad industry is to imagine that Congress decides to give Elon Musk rights-of-way on a 92,000-mile network connecting all major US ports and manufacturing centers. This would make The Boring Company's ambitions look pretty boring by comparison, and would lead to a domestic manufacturing revolution. Now that the railroad industry is on board with higher operating standards that fit well into a just-in-time world and a trend away from offshoring, they start to approach that hypothetical Musk asymptote. Thanks to errors of commission in the 19th century and errors of omission throughout the 20th, North American railroads have gotten massive overinvestment, leading to a wonderfully valuable asset that can keep on throwing off cash for years to come.

Paying subscribers can read Part 2 tomorrow, where we'll do a deep dive on a single railroad and look at what drives their economics and how to value them.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Here's a dirty secret: part of equity research consists of being one of the world's best-paid data-entry professionals. It's a pain—and a rite of passage—to build a financial model by painstakingly transcribing information from 10-Qs, 10-Ks, presentations, and transcripts. Or, at least, it was: Daloopa uses machine learning and human validation to automatically parse financial statements and other disclosures, creating a continuously-updated, detailed, and accurate model.

If you've ever fired up Excel at 8pm and realized you'll be doing ctrl-c alt-tab alt-e-es-v until well past midnight, you owe it to yourself to check this out.

Elsewhere

Smart Margin

At a CFTC roundtable discussing a new futures margin proposal from FTX, a representative of futures exchange ICE claimed that at least one major trading firm technically defaulted early in the Covid pandemic, but was given a pass and ultimately did not collapse ($, FT). The comment was vague on exactly what happened, and didn't specify who it happened to (other than the ominous note that "that person sits in this room, and they know exactly who I’m talking about.")

It's not immediately obvious which is better for financial stability: a system where someone can slightly default and get away with it, or one where market chaos is compounded by the collapse of a trading firm, which would probably take down other firms and perhaps exchanges with it. There are anecdotes here and there about similar situations; in his memoir, Jim Cramer claims that at the peak of the 1998 meltdown, his hedge fund should have gotten a margin call from its brokers, but they didn't get around to it in time and prices recovered. But this also happened with Archegos: when they were asked to put up more margin, they blew off the requests even as the value of their collateral kept declining.

There may be a load-bearing level of forbearance within the industry, especially on the part of exchanges that may know their counterparties are hours away from fixing whatever put them in default. The FTX proposal is designed to get rid of this kind of discretion, automatically adjusting margin demands and liquidating positions in response to market moves. That's more elegant than the current system, because it's more legible, but it may turn out that illegibility is what kept the legacy version running.

Peak College?

College enrollments are down for a fifth straight semester, with community colleges slowing more. This is a Covid trend that hasn't yet mean-reverted, though it may be slower-moving than others. One possibility is that students who attended college remotely realized that they could get a similar experience much more cheaply through coding bootcamps and other alternatives. Even if that doesn't match the college experience or the signaling value, the ROI is still there.

Two-Sided Markets

While EVs are still rising in popularity, with US sales up 85% Y/Y in 2021, there's a shortage of charging stations ($, WSJ). Gas stations and cars had economic models that could work somewhat independently, but it's hard to get the same kind of flywheel going with electric vehicles. One helpful feature is that the gas station business relies on converting foot traffic into sales of non-gas products, and that portion of the business model translates well. State grants for charging stations have been snapped up mostly by established companies; in Texas, 85% of a $21m grant went to Shell and Buc-ees.6

Bonds

China is allowing foreign investors to access its onshore bond market ($, FT) starting at the end of next month. China's bonds have been popular because the country is both large and growing, so it's able to provide better real returns than other sovereign debt. But it's not directly comparable, because the Chinese financial model isn't compatible with fully open financial flows. I've previously written about how this closed system limits China's prospects as a reserve currency issuer. Anything that opens their markets more both improves their prospects of attaining reserve currency status and indicates something about the government's plans in that direction.

Diff Jobs

Diff Jobs is our service matching readers to job opportunities in the Diff network. We work with a range of companies, mostly venture-funded, with an emphasis on software and fintech but with breadth beyond that.

If you're interested in pursuing a role, please reach out—if trhere's a potential match, we start with an introductory call to see if we have a good fit, and then a more in-depth discussion of what you've worked on. (Depending on the role, this can focus on work or side projects.) Diff Jobs is free for job applicants.

- A company trying to build something wildly ambitious in decentralized computing is looking for a Principal Product Designer. (US, remote)

- A company solving a major time sink for developers is looking for a variety of engineering candidates (ML research, devops, backend, frontend etc.) in the Washington D.C. area.

- A company helping financial institutions, governments and exchanges to track financial crime on blockchains is looking for a Snr. Product Manager. Experience working as a data industry-adjacent PM required. (US, remote)

- A company making working capital loans to a traditionally underbanked group of small businesses is looking to add a bizops and strategy lead. (SF)

- A company that is being incubated out of a top VC fund is using web3 tech to improve the way brands can acquire and retain customers. They’re looking for a senior engineer leader, without a requirement for web3 experience. (US, remote)

- We're looking for data engineer roles for multiple companies, including a senior role at an edtech company that would build out the business's entire data team, and a position at a rapidly-growing e-commerce business that's helping expand a novel market. (US, remote)

This was not entirely due to the railroad industry's problems. Penn Central also tried to diversify its way out by acquiring a mix of other companies, including an oil pipeline and the parent company of Six Flags. Penn Central actually did some pretty cool corporate finance maneuvers, including issuing a convertible bond that was convertible into shares of a different company they owned, so they could realize cash from the investment without paying capital gains taxes. They were also pioneers in the use of commercial paper, so their bankruptcy set off a brief financial crisis that nearly killed Goldman.

It's probably best for the most clever CFOs to be at companies that are growing fast rather than dying slowly, though. ↩

At a high level, a good framework for thinking about complements and substitutes in transportation is that 1) the logistics industry as a whole is a roughly 8% tax on the economy, and 2) the big efficiencies have usually been realized in the bulkiest modes of transportation. That means that for any mode of transportation that's smaller than it's competitor has a good chance of being complementary, because it will reduce last-mile costs enough to subsidize more bulk transportation. In the early days of the auto industry, cars were bad for the railroad industry, but trucks were actually good, because they increased the catchment area that could be served by a given provider of bulk transportation. Once trucks started getting more efficient, going longer distances, and getting an implicit subsidy from highways, they pulled ahead. ↩

Railroad Tycoon II is not a great simulation of the railroad industry, since it omits a lot of the land-grant stuff that really drove things, and exaggerates their economic performance to compensate. What the game does well, though, is its stock market simulation, which includes margin trading, short-selling, buybacks, and hostile takeovers. The AI is smart enough to figure out when players are over-levered and short their stocks into oblivion, sometimes crashing the entire market. It's nice for games to have an AI specifically optimized to ruin cheesy strategies. ↩

The one exception is the possibility that there will be a brief moment at the threshold of a positive AGI scenario, in which AI constitutes most of the world's market cap for a brief period before money and markets cease to work in any way we can comprehend. ↩

This didn't just apply to the British. One of the first cases I've encountered of Chinese investment in the US was the merchant Howqua, perhaps the richest person alive in the early 19th century, who invested in US railroads through relationships with Boston merchants. ↩

Thus requiring us to once again increment the count for "events in the near future that were accurately predicted by Neal Stephenson novels." In his latest, one of the characters is the founder of a business that is clearly modeled on Buc-ees, but has transitioned it to fueling EVs instead of gasoline vehicles. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart