One of the things I struggle with as a parent is instilling kids with the right values, as opposed to the values that are popular right now. Weirdly, I hear parents talk about their concerns in the opposite direction: that their kids won’t be quite socialized enough to believe that what’s morally fashionable in 2018 is eternally true. But that’s just silly. Your kids will grow up with very current values unless you make a deliberate effort to change things.

There are two approaches you can use: you can relentlessly propagandize a single set of norms, or you can encourage your kids to see that there are many different ways to view the world, and while they’re definitely neither equivalent nor equal, decent people can hold wildly divergent views. The natural assumption adults make is to extrapolate based on what got more or less acceptable during their lifetime, but that’s a misleading heuristic, because history as it happens is cyclical, but history as it’s written is triumphalist. When a trend stops, people stop writing about it.

I prefer the open-minded approach to the propaganda approach, both for moral reasons (it’s more respectful to the kids) and for practical ones (only a very boring person can propagandize indefinitely without getting bored).

The second-best approach

But how?

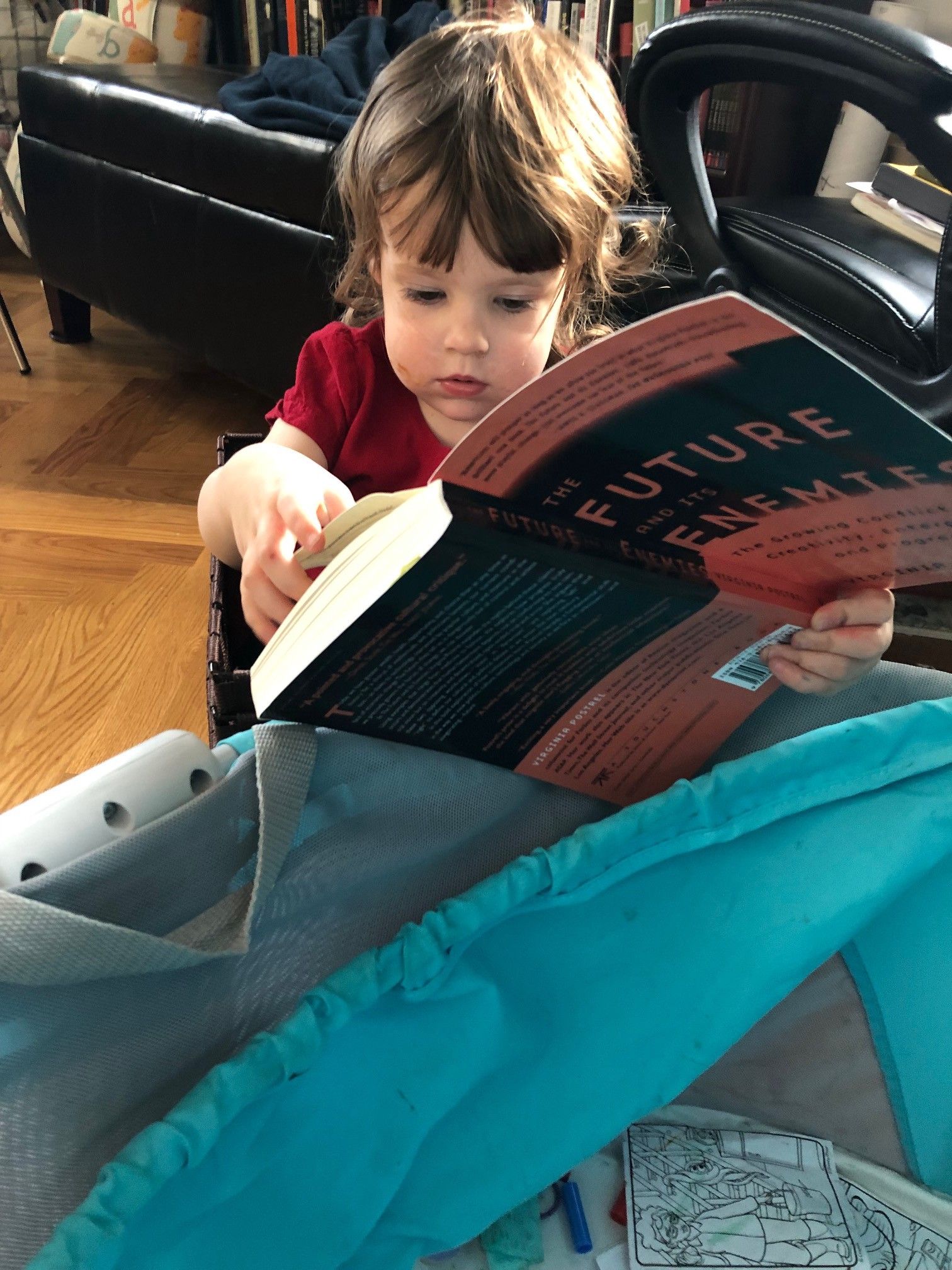

Kids are going to end up watching movies and reading books. And while you can pick out books that deliberately advocate your chosen point of view, you’ll find that unless the viewpoint you choose is mainstream NPR progressivism, the production values will be terrible. There are economic reasons for this: it’s hard to be in publishing if you’re not in New York, and it’s hard to be in New York if your only source of income is a job in publishing, so of course there’s a tendency for the people who pick books to have a left-of-center approach: one way or another, they’re not earning a market income, so they don’t think like people who do.

I’ve found a few kids’ books and movies whose themes echo the work of interesting but out-of-the-mainstream thinkers. Some recommendations:

Hello, Lighthouse! A newish children’s book, Hello, Lighthouse explores traditionalist themes in the face of relentlessly advancing technology — more Wendell Berry than Ted Kaczynski, though. The book also makes Elizabeth Warren’s argument for single-earner households from back in the Two Income Trap days: it gives your household flexibility, since the nonworking parent can always go back to work if the other parent is incapacitated. Also, the art is charming. Hello, Lighthouse is the most underrated children’s book I’ve encountered.

Aladdin explores the same themes as Eric Voegelin: Jafar is nominally a gnostic (with esoteric knowledge of the lamp) but really a power-hungry nihilist, while Aladdin learns an important lesson about immanentizing the eschaton. Aladdin is a movie about the temptations of absolute power, and the harms that ensue once you have it. If you’re powerful enough to create heaven on earth, you’ll probably succeed in creating some sort of hell.

Where the Wild Things Are is a journey out of order and into a Hobbesian nightmare. (And then back to order. (And dinner.)) It’s a good reminder to children that a powerful centralized state serves an important purpose, and also that they should obey their parents.

The Nightmare Before Christmas: people claim that Hollywood is biased against conservative themes, but this movie is proof to the contrary. The plot is that open borders lead to conflict, and the only people who can handle cultural differences are absolute monarchs. It’s basically a restatement of the work of Carl Schmitt. It’s all there: the friend/enemy distinction, the ineffectiveness of representative government at times of crisis (Halloween Town has both a King and a mayor; as soon as the king goes missing, the mayor panics), and of course the sovereign’s prerogative to violate otherwise ironclad rules. Schmitt goes in and out of fashion, but ever since Nixon we’ve been slowly ratcheting up the power of the executive, so he’s worth reading to understand where we are and where we’re going. (For a contemporary view of Schmitt, albeit one not in children’s book form, I recommend The Executive Unbound.

These are not strictly Straussian interpretations of the works cited. For it to be Straussian, you have to assume that the writer is encrypting a belief they have, instead of accidentally arguing for one they don’t. Maybe it’s Found Straussianism. Children’s literature will tend to echo non-liberal themes, for the simple reason that many of the stories are timeless, and conservatism is all about celebrating stuff that appears to work by virtue of its age alone.

My goal is not to raise kids who are my ideological carbon-copies. My parents did better than that, and I’m not a fan of downward mobility. Instead, I’d like to raise kids who can look at a Barnes & Noble display or a list of recommended children’s books or a Very Special Episode and treat it as kitsch rather than dogma. Some people don’t develop this skill, even as adults, but it’s never too early to try.