The Robinhood Challenge

The entire financial services industry is basically a multi-billion dollar R&D project trying to determine a) every conceivable form of agency risk, and b) every possible norm, agreement, economic equilibrium, or (worst case scenario!) law that can balance it out. This has to be true, since the fundamental function of the industry is for people with money to entrust it to people with expertise, and then hopefully get more of it back eventually. The experts are in a better position than their investors to know whether or not they’ve made a best effort, or overcharged, or otherwise misbehaved. Robinhood, which of course filed its S-1 last week, is a shining example of this.

The investor letter highlights how most of Robinhood's customers are long-term, buy-and-hold investors; how the company democratized finance by making zero-commission trades available to average investors; how it targets demographics that other brokers can't or won't reach. But the Management's Discussion and Analysis section of the S-1 tells a different story: the core driver of revenue for Robinhood is to acquire customers and then convert them into crypto and especially options traders. As Matt Levine puts it (emphasis added):

At the end of the quarter, Robinhood customers owned $65 billion of stocks, $11.6 billion of cryptocurrency, and $2 billion of options.[2] You can divide.[3] Robinhood extracted about 0.2% of the value of its customers’ stock portfolios for itself, as trading revenues, in the first quarter of 2021. That is, you know, higher than Vanguard charges (remember, that 0.2% is for one quarter), but Robinhood’s customers are having a lot more fun, fine. Again, Robinhood is a bet that people want to pay up (sort of) for fun investing. Robinhood extracted about 1.2% of the value of its customers’ crypto portfolios for itself, from trading revenues, that quarter. That doesn’t seem wildly out of line for crypto.[4] Robinhood extracted 9.5% of the value of its customers’ options portfolio for itself in the first quarter, $197.9 million of revenue on $2 billion of assets. That’s a lot!

So the profit-maximizing move for Robinhood, right now, is to encourage as many users as possible to switch from buying and holding stocks to day-trading options. But that's not exactly ideal for customers. And it's not great for valuation, either: ideally, if long-term equity appreciation is higher than Robinhood's annual churn, their customer lifetime value can be arbitrarily high, especially because their customers are young (average age: 31) and will keep on adding to their accounts over time. A $5,000 account, all invested in equities, might start out producing $10 in annual revenue this year. But it might end up being a $50,000 or $100,000 account after a decade of saving, producing $100 or $200 in annual revenue instead. On the other hand, if Robinhood convinces that user to switch from holding $5,000 worth of stock to trading $5,000 worth of out-of-the-money options, the account will produce around $1,645 in revenue in year one.1

This is true of many businesses: most people who go to Macau or Vegas gamble a little and lose a little, but those ritzy buildings are paid for by the ones who develop a more serious gambling problem. In gambling, this would be referred to as targeting "whales," who can generate far higher returns per customer than average. (In the literal whaling business, the appropriate metaphor is ambergris.)

The stock market is, of course, a good tool for investing, but it's also a good tool for gambling. Some numbers rackets used stock market data as a random number generator. Low-value gambling tends to combine random number generation with narrative: slot machines apply some kind of thematic skin to the same fundamental game, and daily fantasy sports operate on a similar principle. (As XKCD points out, this also applies to dice-driven role-playing games like the Dungeons & Dragons franchise.)

More than half of Robinhood's investors are first-time investors, and the company says it's responsible for almost half of new brokerage accounts funded in the US since 2016. This means that, for a significant share of Robinhood customers, bear markets lasting longer than a couple months are an entirely hypothetical construct. This kind of thing has happened before: one driver of the 1960s bull market was a confluence of cheaper distribution through mass media and a more affluent middle class; it finally started to make sense to sell stocks and mutual funds to people who weren't rich yet, and the market adapted to that new source of customers. They know, of course, that stocks can go down, but right now retail investors expect to earn real returns of 17.5% annually over time, although the target for 2021 is a more achievable 17.3% ($, WSJ). Since new methods of marketing tend to take off during bull markets, this kind of thing has happened before. The usual result is a lot of money made on the way up, and a lot of recrimination on the way down.

Robinhood itself suffers from some of this (the company was founded in 2013). In their investor letter, the founders allude to Robinhood's low margin loan rates as a credit card alternative. It is true that paying 2.5% rather than a rate in the teens is a good deal, but stock prices tend to lead the economic cycle, while credit lines are a coincident or slightly lagging indicator (per the quarterly Household Debt and Credit Report, total credit limits peaked in Q3 of 2008, about a year after the the S&P). So people who fund expenses with margin debt rather than credit cards will come into a recession already financially stressed, which is not a good place to be when unemployment is rocketing.

Robinhood acknowledges this as a risk, and they even quantify how dependent they are on rising market activity: the S-1 notes that in October 2020, when US equity trading volume dropped 4.8% from the preceding month, their transaction revenue declined by 9%. (There were earlier months with bigger declines in volume, but presumably the secular growth in Robinhood offset that, so late 2020 was the first comparable period.)

Buy-and-hold investors might be disappointed if their accounts don't hit the high-teens threshold, but they're less likely to give up on investing entirely after a bad year or two. Part of why Robinhood is such a lucrative business is that it's found lots of small ways to nudge users towards more frequent trading in more exotic products. But such nudges can work in the opposite direction, too. Robinhood is clearly good at nudges, because it's been able to overcome the usual loss aversion problem: people tend to suffer about twice as much from losing a dollar as they benefit from gaining one, hence the popularity of insurance. On the other hand, people will willingly play games with a negative expected value and frequent losses if they're fun enough, hence the casino industry. A company that can flip users from buying-insurance mode to weekend-in-Vegas mode can probably flip them back.

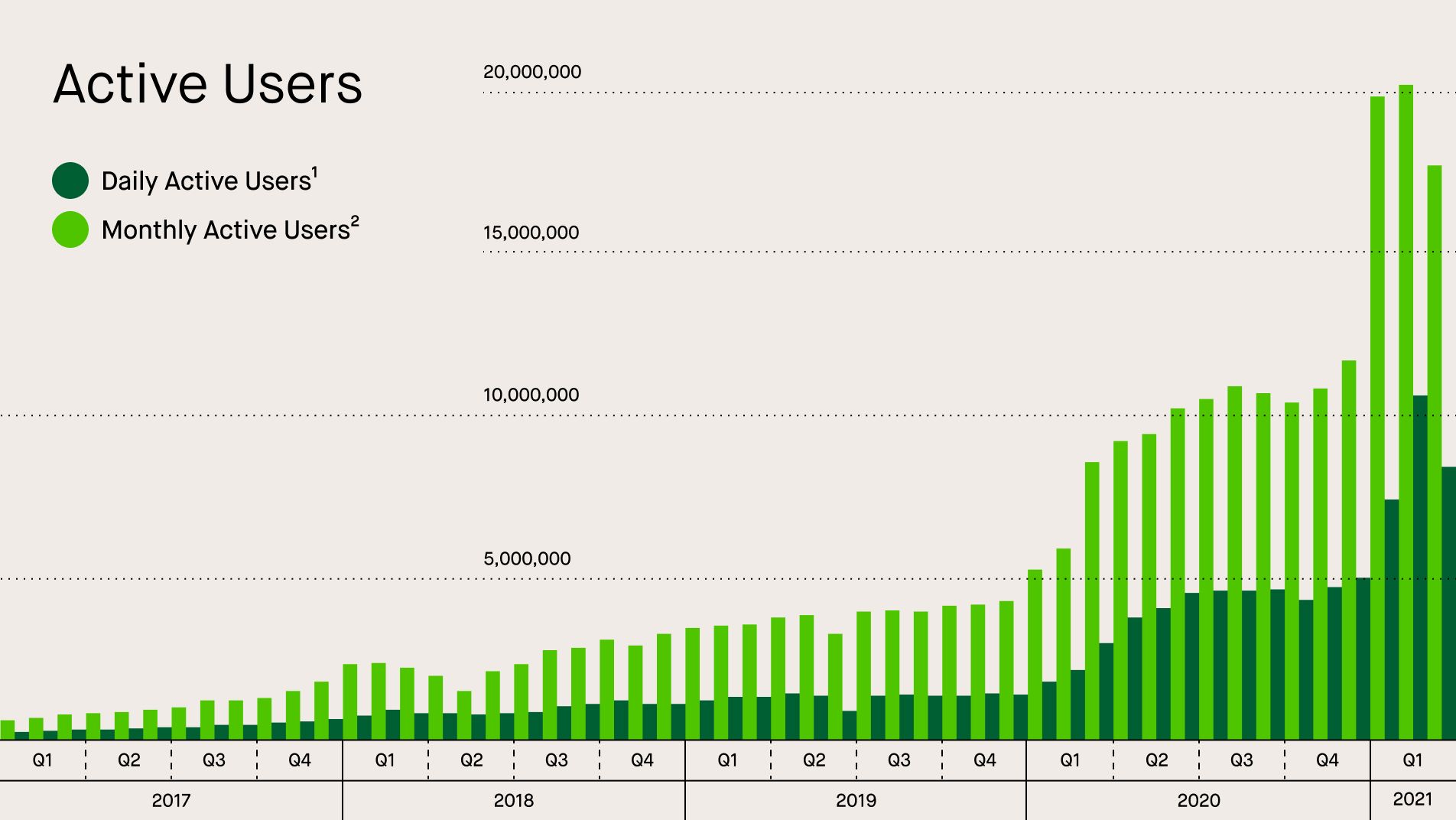

Looking at customer behavior ignores the question of how customers get to Robinhood in the first place, and that turns out to be an interesting story. In 2020, their net funded accounts grew 145%, but their traditional marketing budget actually declined by 14.0% from 2019. The reason: their very successful referral program. Like Duolingo, Robinhood borrows user engagement tricks from casual games. It also integrates them into its marketing. For example, Robinhood's referral program gives new users a single share of a randomly-chosen stock, usually worth between $2.50 and $10. This is a) not much money, and b) in an inconvenient form. But just as game tutorials will introduce players to a new mechanic by forcing them to use it, not just displaying it in the interface, Robinhood's share-based referral program is meant to give new users a monetary reward and get them to make their first trade.2 This is exactly the same reasoning by which a mobile game will a) give the player an in-game power-up that they’ll later be able to buy with real money, and b) convince them to use it. The reward is triggered when users fund their accounts, so it's also a way to reduce the drop-off rate from expressing interest to actually using the app. Interestingly, this was not their first experiment with referral marketing: they let users move up on the app's waitlist by sharing referral links, including through social media.

As a result of this program, and generally high trading volumes, their payback period on new accounts has also dropped; it was 13 months in 2019, and under 5 months in 2020. Normally, a payback that fast is a good reason to expand as quickly as possible, but in this case some of the improvement was driven by the shift from other marketing channels to referrals, and there are hard limits to how fast a company can grow. Robinhood can overcome some of these: the Cloud Infrastructure & Other Software Services opex line item went from $11.8m in 1Q20 to $60.0m in 1Q21. This is as good an example as any of how cloud computing lets companies grow, and by extension how certainty around unit economics helps them get funding: growing a company's infrastructure by 5x in a year is brutally difficult from an organizational standpoint. 15% monthly growth means that if you have a problem big enough that you decide to hire someone to solve it, it can be an existentially difficult one by the time that new hire actually shows up at work. Outsourcing that scale to AWS is a way to reduce the risk, so management can focus on all the other fires they have to put out.

Growth issues are another reason Robinhood might be happy with buy-and-hold customers: day traders create very operational demands. For example, here's how they summarize one set of risk factors:

Our brand has faced challenges in recent years, including as a result of, among other things, the March 2020 Outages, the April-May 2021 Outages, the Early 2021 Trading Restrictions…

(An outage that gets the referred-to-with-capitalized-words treatment from a lawyer is the devops equivalent to this.)

Every one of these incidents was the result of a spike in usage for their most lucrative traders. Each time, they a) signed up a bunch of new customers, and b) greeted many of these customers with a bad user experience, in which they couldn't trade and couldn't contact support. In principle, this is manageable: Robinhood could build its infrastructure, liquidity, and customer service on the assumption that there could be a large spike from some new product or strategy taking off. But those costs get paid upfront, whether or not they're needed. There are some companies that structure themselves entirely around dealing with last-minute crises.3 Financial companies have an unfortunate tendency to set up their cost structure so it's perfect for a permanent bull market right when the market peaks.

Any growth company that goes public will necessarily be going public during an important transition period. Since growth only persists if the company continuously adapts, every part of the businesses' early life involves a series of major inflections. For Robinhood, the change is that they're paying a bunch of fines, making their app less gamey, and talking up their product as a way to save for retirement rather than a tool for gambling. But that's something they may want to take literally, rather than treating it as a sales pitch. Fines are expensive, but their cost in terms of distraction is much higher than that; Robinhood could easily find itself over its operational speed limit because it's growing at the maximum pace it could handle given undivided attention from management—but their attention is being divided by Congressional testimony, legal negotiations, getting the CEO's phone back from the cops, etc.

Any metrics-driven organization without a non-financial long-term goal will tend to operate as the financial equivalent of a paperclip maximizer. When people diagnose corporations as sociopaths, this is what they're talking about. But sociopathic behavior is a subset of normal human behavior; we can all be goal-directed and willing to take calculated risks, including calculated moral risks, some of the time. Most of us, however, constrain that behavior either by adhering to norms that go beyond utility-maximization or by setting long-term goals that are incompatible with short-term sociopathy.4 Companies are similar: even if their legal structure is predicated on sociopathic behavior, the executives in charge will sometimes take actions that fail to Maximize Shareholder Value because those actions are distasteful to them. Robinhood's executives probably don't want to be remembered for running an unusually profitable casino, but probably do want to be remembered for founding a company that democratized investing and survived its growing pains. And, over a long enough period, the cynical money- and reputation-maximizing approach converges with the well-behaved approach; it's hard to recruit engineers and customers if a company is widely believed to be evil.5

When they were a private company, the bull case was that Robinhood would live up to its own hype as a company that could get millions of people to open their first brokerage account and start trading. Now, they've accomplished that, and they're dealing with the consequences—so they've chosen a more refined version of that pitch, and given themselves a more sedate kind of hype to live up to.

Elsewhere

Another Gulf Carrier?

Last year I wrote about the economics of flag carriers, with an emphasis on the ones run by petrostates. They're an interesting economic hedge: an airline does better when there's a rise in tourism, finance, and other elements of the service economy; it does worse when oil is expensive. So it's a natural fit for a country that sells hydrocarbons and doesn't have a well-diversified economy, especially if that country has a source of tourism. Saudi Arabia has enormous oil reserves and a tourist attraction that almost two billion people are religiously obligated to visit, so it's a natural fit. And now Saudi Arabia plans a new airline to compete with the other gulf carriers. The economics of these businesses are a constraint on their scale, but not on their existence: plenty of investors have blown large sums funding airlines, and it happens to be the case that for petro-states, the sums are larger and their availability is anticorrelated to the airline's return. But this still matters, as both a bet on international business travel and a subsidy for it.

Air Buyout

In related news, an investor group has made an offer to acquire Sydney Airport for $17bn ($, WSJ). This may be the strongest reversion-to-status-quo bet imaginable: it's a big deal that's dependent on 1) more air travel, 2) governments' willingness to approve of the sale of strategically important assets, and 3) continued economic ties between China and Australia. Mean reversion can be as interesting to track as inflections, because it's so easy to overestimate how permanent some shifts are.

The AI Layer

Bytedance is starting to sell access to its customization algorithms to businesses unrelated to video sharing ($, FT). As the close of this article makes clear, such filtering can be applied in a content-agnostic way: picking up a critical mass of useful signals is more important than knowing exactly what those signals are. While it's useful to Bytedance as a revenue source (and very useful as a business to call out as a future growth contributor when they go public), it also has interesting inbound potential. It's unclear if Bytedance retains any rights to use data or models from customers, but given the company's recent efforts in e-commerce, a line of business that lets them interact with successful e-commerce operations is probably useful as a source of R&D, not just a standalone business.

Didi and Information Asymmetry

Didi shares are currently down around 20% after the company was investigated by China's Cyberspace Administration over user data sharing and had its app removed from the app store ($, FT). The WSJ notes that Didi had an unusually brief investor roadshow before its IPO, and knew that something like this was a risk ($). There's always some level of regulatory asymmetry when a company lists its stock in one place and does most of its business in another. There's plenty of cross-border investment in the world, but exploiting local knowledge and influence is a persistent source of alpha. If more US investors are worried about regulatory catastrophes in China—not just that US-based businesses will have trouble selling there, but that China-based companies might run afoul of obscure laws—it will create a market for lemons, in which the optimal move is for well-connected investors to tak their politically at-risk companies private once their stock prices fully reflect the worst-case scenario. (The rumored take-private offer for US-listed but China-focused Weibo may be an early example.

Strategic SPACs

Palantir has started investing in SPAC deals, tying the transactions to purchases of Palantir's products. At 28x sales, Palantir can technically afford to do this: if they get a $1m ARR deal out of making a $25m investment, it's valuation-accretive. It's also a decent way for them to align incentives. If their product does, in fact, provide variable but potentially high upside, then it makes sense for Palantir to capture some of it. (They can do this through structuring deals so they get a cut of profits, but a) sometimes the benefits are too diffuse to measure, and b) if their software is really good, it shouldn't just affect how much money a company makes, but what multiple its stock gets.)

It also ties in with a point that Andrew Walker of Yet Another Value Blog makes: given how many SPACs there are, a SPAC that can raise funding when it does a deal has a big advantage. This usually applies to SPACs whose sponsors have lots of capital (so, good for SPACs associated with PE firms, bad for more independent SPACs). High-multiple enterprise software companies are another possible contributor to this dynamic. Their model requires them to be well-capitalized, since they need to be in a position to lose money on customers initially and make money over time. The Palantir SPAC deals are a more exaggerated version of the same cash flow trajectory: high costs upfront, and upside over the next few years.

(See the Diff writeup of Palantir for more.)

That's an average value, consisting of 1) the many accounts that will go straight to zero, and 2) the handful that will excel. ↩

The origin of this referral program is not discussed in the S-1, but I wouldn't be surprised if it came from someone at Robinhood looking at user profitability conditional on different behaviors. Someone who signs up and doesn't fund an account is in one bucket, someone who signs up and immediately starts trading is in another higher-profit bucket. There's probably a connection between how profitable users are and how long it takes for them to go from signed up to making their first trade. Giving them a stock they're going to immediate trade is a good nudge to get them into a higher monetization bucket. ↩

One of them, for example, was the delightfully named Boots & Coots International Well Control, which was in the business of putting out literal fires for oil companies. That business is only intermittently lucrative, but when it’s needed it has a lot of pricing power; customers who delay are literally burning money. Sadly, they're no longer publicly traded. ↩

For an insightful look at the upsides and downsides of "prosocial sociopathy," I recommend Peter Watts' novel Blindsight. ↩

This is probably true of human sociopaths, too. Given robust enough laws and norms governing their behavior, the cynical utility-maximizing approach converges on the prosocial one. They can still be bad people, or at least amoral, but in principle there's no reason they can't be incentivized to behave well. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart