The Dividend Futures Disaster Revisited: Anatomy of a Very Bad Trade

Late in 2019, I put a bunch of work, and subsequently a bunch of money, into a very interesting trade that wound up costing me a decent chunk of my liquid net worth at an inconvenient time. Of all the experiences people had in New York during March of 2020, mine was hardly the worst, but it was pretty disconcerting to lose money fast at a time when a) I was unemployed and supporting a family of three, and b) the job market was not exactly hot given that the chart of initial claims looked like a capital-L rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise.

So, here's a quick story about derivatives, risk management, Black Swans, and a mistake that was about 10% analytical and 90% psychological.

The trade in question was buying European dividend futures. These are an interesting instrument. There are equity indices that let you bet on aggregate stock prices, and options on those indices that let you bet on the timing as well as change in them. Dividend futures are a bit different: they're a way to bet on the composition of returns. A dividend future pays an amount equal to the dividends paid by the index in a given year. In theory, the net present value of a stock, or a portfolio, is the sum of the present values of all future dividends.1 Dividend futures originated as a sort of academic troll: stock prices in the 90s either implied exceptionally high growth expectations or lower-than-usual future equity returns, and nobody who owned stocks wanted to admit that they were overpaying. Dividend futures were supposed to be a way to illustrate this. If futures priced in high dividend growth over time, the growth argument was easier to argue; if dividend futures showed historically normal growth, the only way to explain stock prices was that investors were willing to tolerate low returns.

It didn't really work this way; I have never in my life encountered someone who pointed to ten year out dividend futures as an indicator of growth expectations. But it did lead to a robust market in the futures themselves.

One area where they were very popular was hedging the risk of equity-linked financial products. The typical way this works is that a bank will sell a retail investor a product that delivers some fixed return, plus a fraction of the return from an index. So an investor buy a product whose return was 1% plus half the change in an index, for example. Importantly, these products were often designed to deliver returns based on the level of the index, not the return from buying shares of it. The bank, their counterparty, now has a short position in the index, which they can easily hedge by just buying its constituents. Except that they're not fully hedged: they're short the index level, and long the constituents, which means their net position is still long the dividends from the index. If the index rises 5% and has a 2% yield, the 5% is fully hedged but the 2% is not.

These products are very popular in Europe, and European banks are very reluctant to take risk, even with an edge. Selling a product with an upfront return is easier to model than selling one whose returns trickle out over a multi-decade period, and risk departments get nervous about it. Meanwhile, it's hard to negotiate upfront compensation for a deal when its eventual return won't be known until many years in the future.

Dividend futures provide an answer to this: the bank above can short them to hedge out its dividend risk, and it will be left with a nice clean trade: sell the customer some exposure, use the market to precisely offset this exposure, and be left with a nice clean fully-hedged trade whose profits are known upfront.

But the result of this was that there was a natural seller of dividend futures, and no natural buyer. I decided to step in and be that buyer. Because of this selling pressure, dividend futures implied that the market's expectation was that European companies would consistently cut their dividends every year for the next decade, ultimately reducing them by 25%. But European stocks were certainly not priced in a way that implied ten years of negative growth. And there were a few other games you could play with this, by looking at how the discount changed over time and what this implied about how futures prices would change; futures a few years out tended to snap back up to more efficient prices, while the ones four years out or further all traded more consistently.

With a lot of modeling and a few not-too-challenging assumptions, I got to an expected return on the 2022 dividend futures of about 3% from the discount gradually reverting to normal, and another 6% from the discount getting much tighter as it went from three years out to two. And, since they're futures, they have built-in leverage; the expected return on the actual cash I had to put up was more like 28% annualized—pretty good for what was, fundamentally, a bet on sleepy blue-chip stocks in a sleepy economy! (For much more on the modeling, see my original writeup from 2019, and note that the most correct thing I said my warning that this could turn out badly.)

Here's what happened: I bought the futures at about 114, at a time when my estimate was that the index's dividend payment in 2022 would be about 127.5. Over the next few months, they gradually rose to 120, for a return of about 15% with leverage, or about 75% annualized. I was, in a highly abstract sense, an extraordinarily successful bank robber—take that, Société Générale!

Meanwhile, I was getting worried about Covid, but, paradoxically, not making any trading decisions around it. I did place some orders, though:

My general view on Covid and markets in early 2020 was that they were a sort of apocalypse trade, and the optimal move in an apocalypse is not to sell. You want to buy, on the grounds that if things get really bad the whole system will collapse and you will be broke no matter what, but if the world doesn't end, you will have gotten a good deal.

The futures wobbled a bit in February, and then, over the course of late February through the end of March, as Covid went from a China story to a China-and-Italy story to a global one, they dropped from 120 to 64. I wasn't there for the entire drop; I started shorting European stocks about halfway down, which at least meant I was partly hedged, and then exited the trade a bit before the bottom.

Still, pretty painful, although I did take comfort in the fact that the European banks that made the original structured products managed to lose a lot of money on the trade, too ($, WSJ).2

Looking back, the biggest mistake I made was the sunk cost fallacy. Normally, this refers to a more purely financial decision: you bought at $10, and now it's at $9, so you're going to hold on until you break even. (And then it goes to $2.) But I wasn't trying to break even in monetary terms, I was trying to avoid having wasted my time. Putting a lot of effort into a model for a trade that will work about 98% of the time is risky in part because the other 2% of the time, you'll feel bad for throwing away all your hard work.

And this is one reason I held on to the trade for so long. A rational person looking at European dividend futures in February of 2020, when they were still priced like nothing was going wrong, might have said: Dividend futures are an abstract bet on financial flows and weird market decisions, but they are also a bet on real-world companies' performance in a specific time period. As it turns out, being long dividends in the immediate future was the single worst trade you could make ahead of a pandemic, since even if recovery was inevitable, earnings would suffer for a while. That was not part of my model, and I resisted incorporating it into the model for a long time. Even though hedging by shorting European stocks was profitable, it was the wrong move, because it turned my trade into a bet that either the European economy would be crushed or it would recover very quickly, which is totally different from the original thesis.

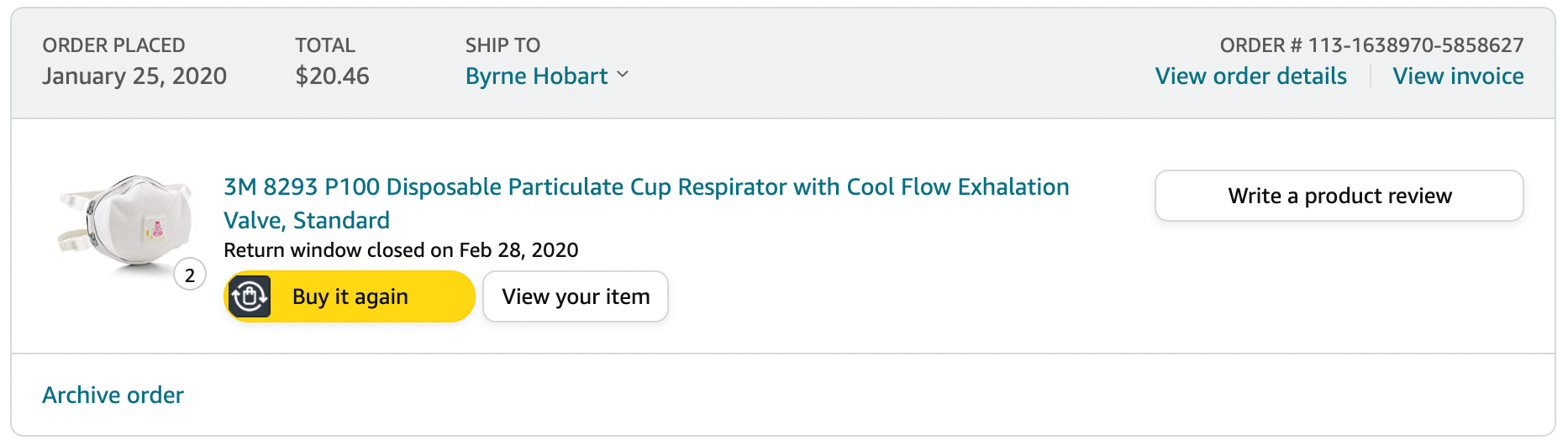

There is a talent to knowing when the rules have changed; there are strategies that work for a while and then start to fail, both in markets and in life, and one of the worst risk-adjusted decisions you can make is to persist in something after you have evidence that it doesn't work the way you thought it did. I could have, hypothetically, had an absolutely spectacular trade in January of 2020 if I'd decided to switch to buying long-term dividend futures (on the assumption that Covid would work itself out at some point) while shorting the near-term ones. Instead, I bought P100 masks. They're still in the box.

All in all, I got a fair deal: I paid about what it would cost to attend an excellent college for a semester or two, and got exactly what a good college promises: not just learning about the way the world works, but learning about myself, too. No sheepskin at the end, but this post will have to do.

Coda

A certain subset of my readers already has this list of dividend futures prices open in another tab, and is no doubt wondering if it's a good time to revisit the trade. The distortions are smaller now; instead of a 25% dividend cut over ten years, they're pricing in about a 10% drop from 2023 to 2030. The near-term futures are really more of a macro bet on a recovery in Europe, which is a perennially hard thing to predict. But what about 2030?

One of the risks I worried about at the time that I did the original trade, which doesn't matter much for stock prices but does matter for dividends, was that European companies would start running themselves a bit more like US-based companies. American companies like to give executives big incentive-based compensation packages weighted towards options, and those executives, in turn, prefer to return cash to shareholders by buying back stock rather than paying dividends. For someone betting on dividends, this is bad news: the dividend futures bet is not just a bet on how much money companies return to shareholders, but how they do it. The Euro Stoxx 50 index trades at 2.2x book value, compared to 4.5x for the S&P 500 (I would use earnings, but current earnings are very noisy since the US index is weighted so heavily to tech companies that kept growing during Covid). If European managers decide to start buying back stock, that will naturally juice per-share growth rates, and some long-abandoned companies will start to look pretty good when they can put up above-average growth numbers merely by shrinking their share count.

This is actually starting to happen. HeidelbergCement plans to buy back almost 7% of its stock over the next two years ($, WSJ), Carrefour is doing roughly half that, Allianz cancelled a buyback late last year due to the pandemic and then reinstated it this month, and overall buybacks in Europe are at a four-year high.

The picture for executive compensation in Europe is also looking increasingly American. Wizz Air, a discount airline, approved a plan to pay their CEO up to £100m in stock if he got the stock to rise by 20% annualized over the next five years ($, FT). This is common enough in the US that you can get good ideas just by looking at which companies are adjusting CEO compensation, and how they time these adjustments. It's much more controversial in Europe, at least for now, but if it works out for Wizz, other executives will ask for the same thing. And that will make the European market look a bit more like the US market, where dividend payouts are low and executives' incentives encourage them to maximize share prices rather than total returns.3

So maybe all that effort was worth it after all: one of the risks I did think about is finally materializing, and this time if the dividend futures trade blows up, I won't be involved.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Here's a dirty secret: part of equity research consists of being one of the world's best-paid data-entry professionals. It's a pain—and a rite of passage—to build a financial model by painstakingly transcribing information from 10-Qs, 10-Ks, presentations, and transcripts. Or, at least, it was: Daloopa uses machine learning and human validation to automatically parse financial statements and other disclosures, creating a continuously-updated, detailed, and accurate model.

If you've ever fired up Excel at 8pm and realized you'll be doing ctrl-c alt-tab alt-e-es-v until well past midnight, you owe it to yourself to check this out.

Elsewhere

I joined Auren Hoffman's "World of Data-as-a-Service" podcast to talk about airline loyalty programs, as well as Bitcoin, newsletter economics, and tax policy.

What's Big on Facebook

Facebook has released their widely-viewed content report, part of an ongoing back-and-forth between the company (which says most people are not reading hyper-partisan news stories) and journalists who use Facebook analytics tools to identify top trending stories and find that Facebook does indeed surface a lot of partisan content. The report is interesting in part because it shows that Facebook spam still works, at least as a way to get attention—Wired has done everyone a favor by looking into why a football team fan site and a CBD store were able to get tens of millions of views (Answer: by posting low-effort memes and including a link). So the report does present a picture of Facebook that's fairly benign: the most popular content isn't inflammatory, just painfully mainstream. This will probably not make the company's critics happy, although it might affect why they don't like the company.

OnlyClothed?

OnlyFans, a site famous for mostly hosting porn, is changing its policies to ban explicit content, though it's not clear yet where the line will be drawn. They cite problems with their payment partners, which is indeed a constraint in that industry. This comes shortly after their financials leaked as part of their fundraising process, showing that the company generated $150m in free cash flow last year and $620m this year. There's a repeating pattern where sites with user-generated content start out as a free-for-all, but slowly tighten the rules. I wrote about this last year, in the context of Reddit banning several subreddits (Reddit survived):

There’s a cycle in many domains: openness is good for challengers and bad for incumbents, so the most successful institution is the one that knows when to be tactically open and when to close up. Reddit started open; in its early days, it was very much a rhetorical free-for-all, with a high tolerance for offensive speech. Twitch is the successor to Justin.tv, which originally livestreamed one guy’s life (the eponymous Justin) and later branched out into other livestreams—including many, many streams of live sports for which the site didn’t have rights. Open again. YouTube also had its share of pirated content (time-shifted rather than live), which it’s since dramatically reduced... Openness wins because an easy way to get a monopoly on some kind of content is to be the biggest site that doesn’t ban it. But “winning” means being a bigger site, with more PR scrutiny, more advertisers, and more employees, so if there’s anything unacceptable to x% of any important constituency, as the site grows x% multiplied by the size of that constituency will eventually reach 1.

One reasonable question to ask is: why would a company that's on track to generate $620m in free cash flow this year want to risk ruining their business model in order to raise outside money? Why not stay private and just pay the owners a dividend? One possibility is that OnlyFans' prospective investors made the company more aware of some of the risks it's running; age-verification is imperfect, and it only takes one headline to make payment partners reconsider doing business with them. There are payments companies that specialize in high-risk transactions, but it's a tough business, and getting tougher; the natural network effects in payments mean that their relative economics get worse over time, and payment supply chains will always include some companies that care about their reputation. Even if the payments are routed through risk-insensitive participants, if someone is paying for OnlyFans with Mastercard and a site user is withdrawing their earnings from Wells Fargo, that's an avenue for bad PR to companies that care a lot more about their public perception than about the fortunes of one low-status startup.

Elite Overproduction as Risk Aversion

Robin Hanson has some thoughts on the concept of elite overproduction, which he ties to tournament-style competition for a limited number of spots. If there's a surplus of people who qualify for whatever position you have, you're much more concerned with minimizing variance than maximizing upside. And those default status markers are much more visible; it's expensive but not hard to hire people who have Ivy League degrees, good test scores, and a decent work ethic, but if a company wanted to find someone with the risk tolerance of Lord Miles, they'd have a hard time producing a list of candidates. Having trusted hierarchies for low-risk behavior and no good ones for high-risk behavior is a good way to ensure that elites never rock the boat, which is fine until the boat runs aground.

A Second Cleantech Boom

One of the points many tech investors made in the 2000s and early 2010s was that the rise of big tech companies had almost nothing in common with the 90s bubble: the Internet was real, and the businesses had profits. A similar dynamic is taking place in cleantech, on a similar delay: the newer companies are bigger, and more profitable ($, Economist). One source of their profits, though, is the price-insensitivity of the customers:

Amazon [has launched a decarbonization investment fund] worth $2bn, financed entirely from its balance-sheet. As such, says Matt Peterson of Amazon, investments need not meet any internal rates of return. “The focus is on decarbonisation, which is a strategic need for Amazon,” he explains. Success will be measured by how much investments reduce Amazon’s carbon footprint.

There are precedents for this working out, and not just at Amazon. It's analogous to East Asian industrial policy, where companies weren't required to be profitable upfront as long as they could hit quantifiable goals that indicated that they could be profitable in the future. Especially at Amazon's scale, it makes sense to get exposure to as many experience curves as possible, and identify the ones with the most favorable slope, before doubling down (or 100xing down, as the case may be).

Disclosure: Long Amazon.

Chip Consolidation

In a WSJ interview, Intel's CEO says the company is eager to consolidate the chip fab industry ($). It is striking that every time there's a new node, there are fewer companies that can successfully build chips, and it's an open question whether this is purely a matter of scale (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing and Samsung are both massive companies) or also a technical/organizational limit. And it's an important question, because it determines whether or not China can stop relying on those companies for its own electronics exports.

Channel Shifts and Comp

Changes in distribution affect who has long-term pricing power, but, especially in the media business, they can have short-term effects from people who signed particularly lucky or unlucky contracts. George Lucas famously secured merchandising and licensing rights for Star Wars, an economic incentive visible in his invention of the Ewoks. More recently, Disney has been in litigation with Scarlett Johansson over her cut of the proceeds from Black Widow. Her contract was signed in 2017, before Disney had launched Disney+ and well before they considered using streaming as the main venue for launching new movies. Disney's strategy in this lawsuit seems strange; there isn't any particular reason that actors' negotiating power would be worse with streaming than with theatrical releases. Obviously her deal was structured in a way that assumed a big theatrical release, and subsequent changes in the movie industry made that a faulty assumption. But Disney has more to gain by retroactively adhering to the deal as it would have been written in 2021, rather than saving a bit of money upfront and making it harder to hire talent in the future.

Technically you want to add acquisitions to this, but buyers are mostly buying a company in order to get the net present value of its future profits, so you're still getting paid on dividends. The exception is a strategic acquisition where the acquirer pays a premium based on, roughly, the net present value of the harm the target will do to them if it stays independent. For a big index fund, this is not an important consideration, because the companies are all so established that they're viable on their own. While there still could be strategic acquisitions in that case, they'd be obvious monopolies. Boeing would pay a big premium to buy Airbus, and Airbus would do the same to buy Boeing, but it's not remotely likely that such a deal could happen. ↩

French banks have been surprisingly important in the development of the equity derivatives market, probably because of France's excellent math and engineering schools. It's been a trend for a long time—a French financial researcher beat Einstein to modeling Brownian motion, while writing a PhD thesis on options pricing. ↩

This is not the place to rehash the dividends versus buybacks debate. Most of the common criticisms of dividends apply perfectly well to buybacks, and I do wish companies would reinvest more of their profits rather than redistributing them in the hope that somebody else had a good idea of where the money should go. Internal hurdle rates for investments have gone up relative to interest rates, so in effect the standard a new investment has to meet has risen. But it's very hard to solve a problem when it's a shared perception of thousands of MBAs at Fortune 500 companies, rather than some kind of policy dial that can get turned or un-stuck. If this does change, it will probably be because of respected companies like Amazon (disclosure: long) and Blackrock, which are clearly willing to deploy capital at lower hurdle rates as long as the returns they're getting exceed their cost of capital. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart