What Works in SaaS Pricing

It's always fun to sell a product with close to zero marginal cost, because in one sense it's impossible to mess up: price too low, and you're still recouping your marginal costs unless you're doing something terribly wrong. On the other hand, recouping the fixed costs is much trickier, not to mention getting the maximum return on sales and marketing expense. So there's wide room for error, but one category of error is pricing at a point that makes a company a nice side project or a steady lifestyle business, when it could have been a unicorn instead. Running a lifestyle business is satisfying for many people, but running one that could be bigger is its own kind of risk, since it creates the potential energy for a more growth-focused competitor—as Lenin would definitely put it in 2022 (he'd work in growth equity1), you may not be interested in the venture-backed growth model, but the venture-backed growth model is interested in your customers.

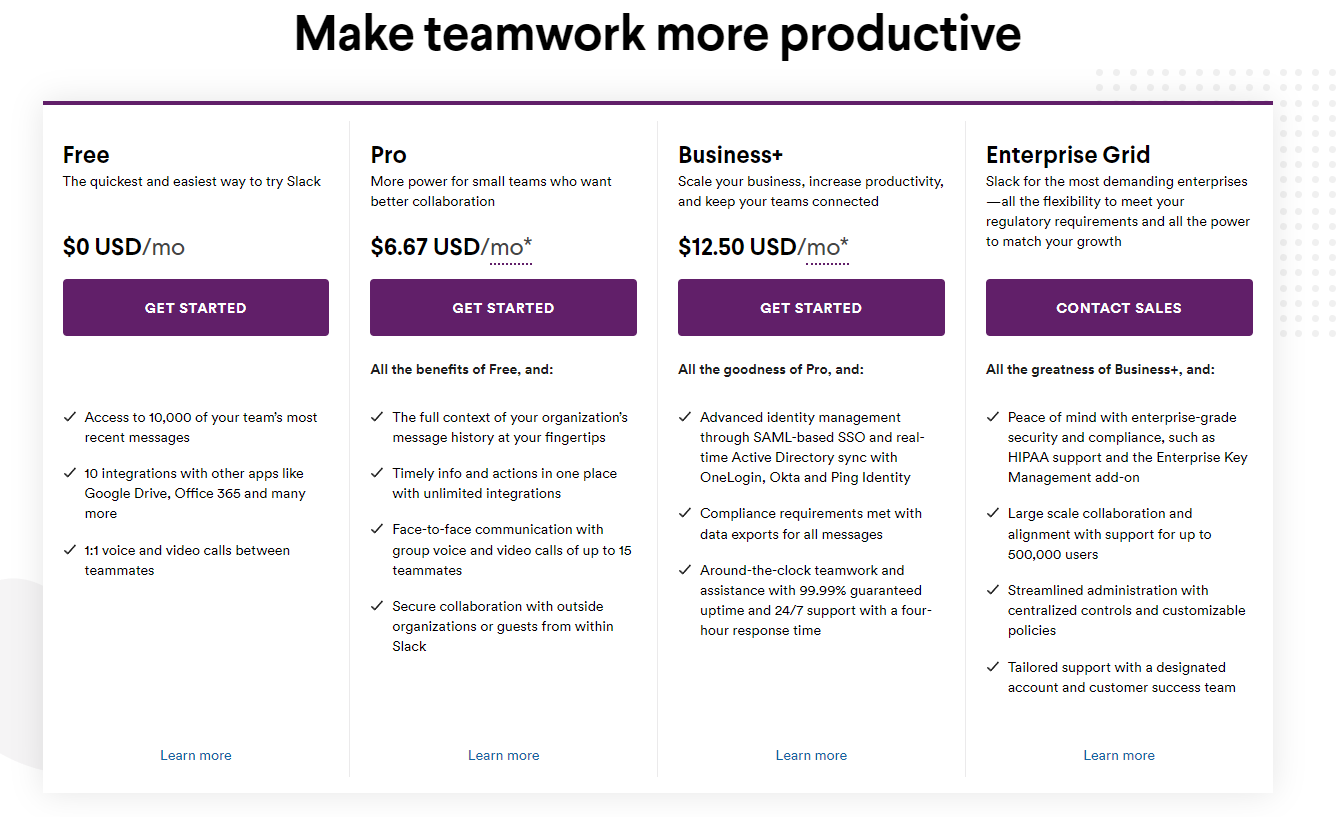

If you've spent much time at all buying software, you've encountered pricing tier pages like these:

For this post, we took a look at fifty such pricing pages from SaaS companies, and broke things down by comparable features. Upfront, pricing choices can be arbitrary, and they can drag a company into local maxima. (You might be able to sell fundamentally identical products for $10/month and $50/month—consider an e-sign product targeting freelance writers versus one targeting lawyers.) Over time, they start to reflect where customers see the product adding value, and which high-spending customers happen to have which specific needs. Pricing pages are furiously A/B-tested both because there's a connection between pricing and revenue and because the results are so measurable: if a feature gets added to the "pro" plan and it shifts a point or two of share from the "basic" plan, that's visible right away.2

One element of price discrimination is to find a feature with a marginal cost, and bracket accounts around how much of that feature is available. The exact feature varies by product—for newsletter platforms it might be subscribers or emails sent per month, for services like Zapier and Automate it's actions, for CRM services it's contacts, for survey sites it’s number of survey answers. There are a few patterns here:

Some companies ratchet this up in a noisy but fairly linear way: Agile CRM's contacts per monthly dollar of spending is 300 at the lowest and highest paid tiers, and 200 in the middle. Engagebay's monthly emails per dollar jumps from 200 to 500 in their middle tier, then stays exactly the same one tier up.

For some companies it's nonlinear all the way up. URL shortener Rebrandly tracks 25,000 clicks/month for its cheapest tier; the "Pro" tier gets 96% more clicks tracked per dollar, and the "Premium" tier is 78% higher than that.

For some companies, there's a rise and then a plateau: Buffer (scheduled social media posts) allows ten posts per channel for all of its free plans, and 2,000 for all of its paid ones. SEO tool Ahrefs has some uses-per-dollar metrics that go down at their highest pricing tier. In these cases, the discontinuity seems to be the point at which customers become price-insensitive as long as they don't have to ration their usage, and rate limits exist more to prevent edge cases that abuse the product than to actively price-discriminate.3

Storage itself is an interesting avenue for price discrimination, since it's cheap for the seller but also limits what the buyer can do. Storage limits (or, for site hosting companies, bandwidth limits) are a sort of universal usage throttle—a way to get customers to upgrade to a higher tier when their activity with the product indicates that they're getting a lot of value out of it.

For storage, nonlinearity is the rule. WordPress offers 7x the storage per dollar for its Business tier relative to its Personal tier, and for G Suite the ratio is almost 60x (G Suite Starter is $6/month and includes 30GB of storage, while G Suite Plus is $18/month for 5TB of storage). Dropbox naturally emphasizes storage costs for lower tiers, while their highest is technically unlimited. (Technically, they still set a quota, but you can ask support to get it raised as often as you want. This serves two purposes for Dropbox: first, it's a decent way to avoid accidental or malicious abuse of unlimited storage, and second it's valuable market research—few companies care more than Dropbox about what the most storage-intensive kinds of business practices are, and what else such customers value.)

Part of the utility of offering storage is that it's a nice ancillary to other products, but another part of the utility is providing buyers with a measurably nonlinear benefit to upgrading. Some purchasing criteria are boolean (and more on that in a bit), but it's nice to have a quantifiable one where it's always feasible to provide enough of it to make low tiers usable while offering ever-escalating quantities to make the higher tiers look like a bargain.

The last notable category is security, logging, and access controls. For many companies, this is what defines the gap between buying an off-the-shelf plan and getting on a call with a sales representative who is tasked with figuring out exactly what you can pay and then backing into what you'd be willing to pay for. SSO, for example, mostly shows up in either the highest priced tier or as a feature available only for enterprise deals with custom pricing.

"Security" in general sounds like a category that should be must-have just about everywhere ("For our 'Basic' plan, we're just uploading your login credentials directly to a blackhat forum; for 'Premium' we upload md5-hashed passwords, and for 'Business' accounts we go the extra mile and hash passwords with a function that takes entire minutes to crack!") But there are limits. For some environments, giving administrators access to everyone's files is an anti-feature, and strict requirements like multi-factor logins slow users down and thus impede adoption. But once companies get to the point that they need SOC 2 compliance—a requirement that can be imposed by outside partners rather than from an internal mandate to worry about security—it becomes critical. Larger companies also scale to the point that they need access controls on some data (if you're storing employee comp in an Excel sheet somewhere, employees will find it4).

Which gives emerging companies a nice pricing strategy: they can start out targeting smaller companies that mostly deal with smaller companies. As they get customer feedback, and play around with A/B tests, they'll start to see which features drive more conversions and upsells. Their first sale to a large company can be a pain in this model, since they have to figure out security—but the first big prospect that's actively interested in their product is probably willing to pay significantly more than smaller companies (though this compliance, too, is turning into a software product). Finding out which features are better as they scale, versus which ones larger customers want to have uncapped access to, opens up new pricing dimensions. And for the truly commoditized stuff like storage, there's room to make every pricing tier measurably more attractive than the last.

Disclosure: I am long AMZN.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Don’t rely on headlines to make the big decisions. Bismarck Brief is the essential newsletter for navigating the global strategic landscape. Every week, subscribers get a long-form analysis of an important institution, industry, or individual that is key to understanding the state of the world.

You can expect in-depth reports on George Soros’ philanthropic empire, the Russian military reforms, the long-term strategy of the Blackstone Group, and much more. A free sample report on China’s space industry is available for download here.

Each Brief is an in-depth case study examining institutional function and the strategy of live players, based on the methods developed by Samo Burja. Samo is President of Bismarck Analysis, which helps companies, governments, philanthropists, and investors gain insight into the fundamentals that drive world events.

We invite you to subscribe today and join us on this ongoing exploration of the global state of play.

Elsewhere

Reformatting Competition

The EU has agreed to new rules on tech competition, limiting large companies' ability to pool data across services and limiting their ability to bundle products and cross-promote their own services. Some of this will still require judgment calls (is Yelp a review app or a map app? Do ride-sharing sites need to promote public transportation?). The most interesting detail is the call for messaging platforms to interoperate. As one ex-Facebook employee notes, this is not quite the anticompetitive salvo it looks like:

As The Diff has argued before, the big tech companies are all intimately aware of one another's competitive advantages, and how those advantages continue to be bolstered. And many of their behaviors are built around weakening other big tech companies in order to defend their own turf. Messaging is a particularly tricky area, because it's such a driver of habits and repeated app engagement. And once there's interoperability, competitive dynamics change so each company has a stronger incentive to build a more compelling frontend once they're all sharing the same network. (Meta might have the biggest advantage there: it has more signals of who's likely to talk to whom than Apple does, since it can look at profile views, likes, and other indicators of the overall strength of social ties and the timeliness of a messaging interaction. That's harder if data can't be shared across different apps, though.)

Ending Oil Won't End Energy Politics

The Economist has a fascinating look at which countries will be energy superpowers in a world with more renewables ($, Economist). Renewables don't require much in the way of incremental raw materials to keep producing power, but they do require a lot to start. And as it turns out, the world of "green metals" exporters is actually more concentrated than that of hydrocarbons: the top ten exporters of oil and gas both have collective market shares of a bit over 70%, while the shares for cobalt, silver, lithium, zinc, aluminum, nickel, and copper are all higher. (For cobalt, there are eight exporters, and one, the Democratic Republic of Congo, has more than 70% share.) So the difficult calculations oil and gas importers have had to make in the past will apply in a green future, too. There are more options to delay than there are with oil and gas—but at the cost of, well, using more oil and gas.

The Bullwhip Effect in Discounters

Shipping delays and higher shipping costs have had a surprising side effect: retailers that sell off-price goods are actually doing better, because shipping disruptions mean that more goods are arriving too late to sell at full price ($, WSJ). This is partly a testament to how effectively larger retailers have handled supply chain issues: they were able to mostly keep goods in stock, at enormous cost, even though some of that cost went to buying products they ultimately elected not to sell. But if large retailers did fine, and large discounters did, too, this implies that smaller companies lost share at a time when consumer spending was unusually high. Post-Covid fiscal policy skewed towards benefiting small businesses (PPP loans were great for them, and since small companies sell more into the domestic market, generally high spending helped them more), but the post-Covid recovery has generally helped bigger ones.

Russia's Gold

Of Russia's FX reserves, the dollar- and euro-denominated portions are difficult to use because of sanctions and asset freezes. But the country also has the world's fifth-largest gold reserves. The G7 plans to apply sanctions to them, too ($, FT). One interesting feature of gold as a reserve asset is that even if a country can't use its FX reserves externally, gold is one that can be used internally instead, and part of Russia's near-term economic policy is to manage the value of the ruble as a proxy for managing the popularity of the war.

Meanwhile, the US plans to send more LNG to Europe ($, FT), though there are questions about the logistical feasibility of getting it to places that consume Russian gas. And Chinese companies are quietly buying Russian oil. Sanctions don't exist in a steady state, and can be escalated if the first round doesn't work. But expanding them means taking action against companies and countries that may view their own behavior as neutrally taking advantage of energy market disruptions, rather than choosing a side.

Negotiating Governance

Funding terms for startups have gotten more founder-friendly over time, which is most visible in the valuations. But it also affects control: for a given percentage stake of the equity, funders are accepting fewer board seats and other restrictions on companies, especially in crypto ($, FT). There are a few reasons for this: first, corporate governance and control can be incredibly tedious to negotiate, whereas with valuation it’s just a lot easier to bat numbers back and forth until there’s an approximate agreement. Second, liquidity is a substitute for control, and especially in crypto it’s possible for backers to convert their gains into cash much faster than has been the case with other kinds of startups: Hirschman gets cited a lot in crypto circles, and in a company context it’s worth thinking about the tradeoffs both for the party choosing between exit, voice, and loyalty and for the institution offering one of the three—voice slows down iteration, loyalty is hard to earn at scale, but exit is actually easier to offer at scale. The downside for companies is that if exit is the best corporate governance option, they’re one misstep away from losing access to funding. But that’s a risk many companies willingly take.

Diff Jobs

- A company improving the fund closing process for VCs is looking for a product manager. (NYC)

- An alternative data consultancy working with hedge funds is looking for a data scientist. (NYC, remote)

- A company offering crypto-denominated life insurance is looking for a Chief Insurance Officer. (US, remote)

- A quant shop is looking for quant developers and quant researchers. (NYC)

- A company helping small businesses access government incentives is looking for frontend engineers. (US, remote)

- A company building an emerging market bank for SMBs is looking for their first Head of Product. (London)

One of the underrated prosocial aspects of financial markets is that they provide an outlet for ambitious and unscrupulous people who delight in zero- and negative-sum games. These people will exist no matter what, and they're a lot less harmful when they negotiate aggressive deal terms instead of doing something atrocious in government or the military. ↩

One piece of evidence that they're so heavily tested is that some of the minor details are inconsistent between live pages and the pages from a week ago when we gathered the data. ↩

What kinds of edge cases? If you're sufficiently cheap, dedicated, and risk-tolerant, anything with "unlimited storage" can be hacked into a cheap alternative to S3. This would be a catastrophically bad idea, and you'd probably lose your data if you did this, but you might be tempted, and rate limits are one way to reduce this temptation. They're also a way to reduce the risk of, for example, a newsletter or CRM service being used to send spam, free-riding on the sender's status as a reputable emailer. And even if behavior isn't malicious, it can happen through simple incompetence. I have personally amassed an impressive accidental AWS bill by using a complicated formula that was supposed to join two tables but accidentally produced their Cartesian product as an intermediate step. They were not small tables.

AWS, notably, is not included in this analysis, both because its pricing is so usage-dependent and because an analysis of AWS pricing could fill multiple books (though you’d really want a book-length wiki). There's an entire company dedicated to helping businesses understand their AWS bills, not to mention many full-time employees worth of effort trying to reduce those bills. And, of course, there's plenty of effort going in the other direction. Amazon employed 150 economics PhDs as of early 2019, compared to 400 at the Fed. ↩

Source: Once found it, promptly negotiated a raise. ↩