You And Your Investment Research

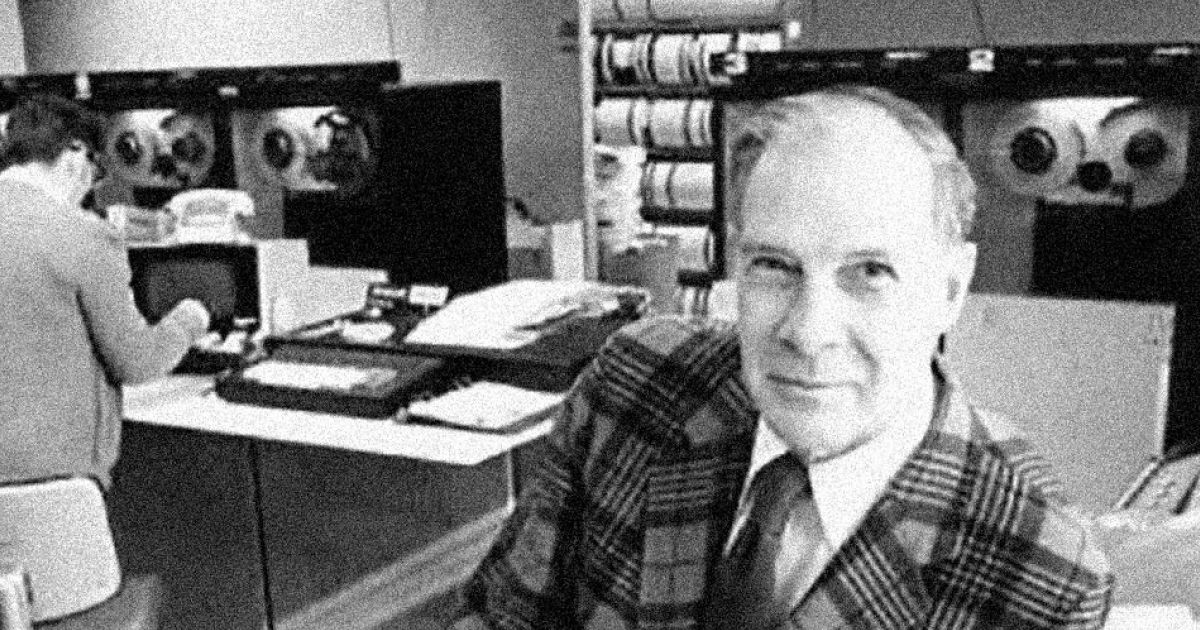

It's hard for a non-expert to evaluate a mathematician, but by the simple proxy of how many concepts other mathematicians put his name on, Richard Hamming has to be one of the greats; he worked on Hamming Distance, Hamming Codes, Hamming Matrices, the Hamming Window, Hamming Numbers, and Hamming Bound. Most of this work revolved around the question of how to transmit information with perfect accuracy as pithily as possible, so it's entirely appropriate that he also produced a classic talk that briefly summarizes how to make immortal contributions to science and mathematics, called You And Your Research.

The high point of the piece is this anecdote:

Over on the other side of the dining hall was a chemistry table. I had worked with one of the fellows, Dave McCall; furthermore he was courting our secretary at the time. I went over and said, "Do you mind if I join you?" They can't say no, so I started eating with them for a while. And I started asking, "What are the important problems of your field?" And after a week or so, "What important problems are you working on?" And after some more time I came in one day and said, "If what you are doing is not important, and if you don't think it is going to lead to something important, why are you at Bell Labs working on it?" I wasn't welcomed after that; I had to find somebody else to eat with! That was in the spring.

In the fall, Dave McCall stopped me in the hall and said, "Hamming, that remark of yours got underneath my skin. I thought about it all summer, i.e. what were the important problems in my field. I haven't changed my research," he says, "but I think it was well worthwhile." And I said, "Thank you Dave," and went on. I noticed a couple of months later he was made the head of the department. I noticed the other day he was a Member of the National Academy of Engineering. I noticed he has succeeded. I have never heard the names of any of the other fellows at that table mentioned in science and scientific circles. They were unable to ask themselves, "What are the important problems in my field?"

Now, to be fair, Hamming is cheating a little bit by having these conversations at Bell Labs, which at the time was one of the densest concentrations of smart people in history. Results may vary if your lunch options do not include a choice of which Nobel Prize winner to eat with that day.

But it's a good thought experiment, and it can work in other domains.

It's especially powerful in investing, a field where most of the opportunities are available to anyone—you don't need expensive lab equipment to trade stocks or futures—and because there's a huge community that can provide feedback or criticism.1 There is also, very conveniently, an independent way to judge who was both contrarian and right; realized capital gains don't lie.

The returns from investing are incredibly nonlinear, and mostly come down to a handful of decisions. This is visible in areas like venture capital, where it's literally true at the level of individual investments. (In Secrets of Sand Hill Road, Scott Kupor asks a fun quiz question: what was the performance of the rest of the investments in the Accel fund that backed Facebook? Answer: nobody knows or cares, because the results from Facebook were so overwhelming.) For quantitative strategies that make more frequent trades and run more diversified portfolios, there's still skew in which signals generate big returns and which ones have more modest results, although it's less extreme.2 And for traditional stock-picking, it's also true: over a twenty-year period ending in 2017, the median stock in the S&P produced a 2.0% annualized return, compared to the 6.1% return from the index. Over longer periods, it's even more stark: start the clock in 1926, and only 4% of stocks make a positive contribution to the market's overall returns.

It's hard to perform a strictly quantitative evaluation of this claim, because there's a lot of noise in the data. But looking back you can often disaggregate a career into a huge amount of work that didn't produce much of value, and a tiny amount that more than compensated for this. And, typically, the bigger the success the more dependent it is on a tiny number of decisions. You can look at those decisions as retrospectively answering important questions. And the right response to this is to go looking for those questions, and then answer them.

For example:

In enterprise software: why is everyone trying to own passwords and user authentication, and who will own it? It's obviously valuable, but not obvious that everyone who's fighting for this will win (latest contender: Box). If a few companies were working on this, it would look like a nice-to-have feature that might help them more easily sell other products; if lots of companies are doing this, the implication is that 1) it's quite important, not just a nice additional feature, and 2) there isn't yet a clear winner.

In energy: is the world actually going to transition to low-energy emissions any time soon? It's not the only answer to global warming—geoengineering, starting over with another planet, or some kind of catastrophe that kills most of the carbon-emitting humans will also do the trick. But it seems to be the main one to focus on. While there are promising signs—China, the biggest incremental emitter in recent years, has stopped funding overseas coal projects, while in the Middle East renewable energy projects are getting more funding than fuel-based power plants. But there's a big difference between a world where hydrocarbon use grows slowly and one where it's rapidly displaced by alternatives. There's also a big difference between a world where publicly traded energy companies divest their dirtiest assets to private companies or state-run ones that run them the way they've always been run, and a world where the most polluting fuels stay in the ground.

In macro: is runaway inflation happening, or not? I've been in the "it's transitory" camp for a while (see here ($), here ($), and here), and one of the best defenses of the transient inflation view is that real rates, as measured by inflation-protected bonds, are quite negative (right now, -1.13% for 10-year bonds). But those real rates may not be very real after all, because the Fed is buying a disproportionate number of inflation-protected securities ($, FT). Why would a central bank do this? Regular bonds are much more liquid, and part of the point of quantitative easing is that it has low transaction costs. One reason to do it is because people look at low real rates as an indicator of future growth expectations, and expansionary monetary policy is easier to justify if growth expectations are low. If that's what's going on—a big "if," since this is both one theory of many possible theories and a bit of a conspiracy theory at that—it implies that actual inflation expectations should move inversely with market inflation expectations.3

In venture, at least a few VCs in the 2020s will back some company X such that in the 2030s, everyone is hoping to back "the next X." The better an investor's career, the more it depends on finding that X, or, ideally, finding X a few decades in a row.

A mediocre growth investment is a company that's growing at an above-average rate right now and that trades at a premium price; a great one is the company that is already planning for what will make it an above-average grower in 2026 and 2031. These companies are exceptionally rare, because merely managing existing growth is already a challenge that requires a supremely competent executive—just look at cyclical companies, which go through short-term growth spurts and have to grab revenue while they can without larding themselves up with high costs. A growth company carries the same challenge as a cyclical, but has to manage one upcycle while somehow inventing the next few. Sometimes starting a startup gets compared to jumping out of a plane and assembling a hang glider on the way down, but the FAANGs have all been through huge business pivots while sustaining growth, so to take the analogy further it's a bit like assembling a hang glider while also inventing a jetpack. The task for growth investors is to identify the handful of management teams that will be able to surf to the next S-curve.

People naturally shy away from confronting these big problems. And that's reasonable: the success rate is low, and it's doubly egotistical to focus entirely on one problem: it implies that you know better than everyone else what ought to be worked on, and that a big outstanding problem is one that you, personally, can solve.

In fact, you can sometimes see this difficulty in why people quit. Hedge fund managers often write a letter to investors when they quit, explaining their decision; they are either giving clients the disappointing news that they'll stop generating so much money for them or the equally disappointing news that they don't expect to make back what they lost. In recent years, some of these letters have talked about why the market doesn't make as much sense as it used to, blaming index investing, mysterious algorithms, gung-ho retail investors, or the Fed. But embedded in each of those is a big, important question:

- Index funds are, fundamentally, a bet that the cost of adverse selection from bad stock picks is lower than the cost of hiring someone to make good stock picks. It is humiliating to be beaten at the job of collecting assets and charging fees by someone whose entire premise is that the way do that job is wrong—it’s losing a game to someone who refuses to play. But index funds either create price distortions or they don't. If they do, managers can find ways to take advantage of them, whether that's a sophisticated strategy based on taking advantage of fund flows or a lateral thinking approach like investing in private companies that will, in effect, be flipped to index funds when they IPO.

- Have quantitative investors collectively spotted big market inefficiencies that discretionary investors used to find through other ways? Or are the quants pushing prices in the wrong direction—and, if so, what's the endgame?

- If the average AMC/GME call buyer is right, valuation doesn't matter. In the short term, if a stock is heavily shorted and the retail investors move fast enough, they can turn hedge funds into money piñatas, but over time, a strategy of engineering short squeezes only works if a) the retail buyers can buy enough to move the market, but not so much that short-covering isn't offset by day trader selling, and b) they're socially, technically, and legally able to coordinate their behavior.

- If the Fed is always going to bail out equity investors, what that means in the short term is that it's hard to short stocks. But in the long term it creates newly complicated questions: if the downside from owning stocks is lower, the risk is lower, but market efficiency dictates that this makes future returns lower, too. But that implies one of two things: either there is some category of risk that used to exist and has been compressed or even eliminated, or there's still risk somewhere and everything is priced as if there isn't any.

Getting quarterly earnings right is a fun game, and day-trading futures is certainly entertaining. But ultimately those behaviors are about precision rather than accuracy; they implicitly assume that the general models we're working with are correct, and that the best use of time is to fill in the details. Hamming is right: it's possible to pick a problem, obsess over it, and find a unique answer; that's how his name got on so many mathematical constructs, and that's what separates a good quarter or a good year from a good career.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Here's a dirty secret: part of equity research consists of being one of the world's best-paid data-entry professionals. It's a pain—and a rite of passage—to build a financial model by painstakingly transcribing information from 10-Qs, 10-Ks, presentations, and transcripts. Or, at least, it was: Daloopa uses machine learning and human validation to automatically parse financial statements and other disclosures, creating a continuously-updated, detailed, and accurate model.

If you've ever fired up Excel at 8pm and realized you'll be doing ctrl-c alt-tab alt-e-es-v until well past midnight, you owe it to yourself to check this out.

Elsewhere

A Successful IPO from Robinhood

Robinhood's IPO priced at $38, and the stock closed yesterday at $34.82, which is obviously a very poor performance for a large IPO. One reason for the unusual performance was the offering's unusual structure: they allocated shares directly to retail investors instead of selling them to institutions who would later flip them. The general problem Robinhood faced was that price-insensitive retail traders were likely to buy at the first price they got, which would either be the IPO price (if they bought directly) or the first price at which the stock traded (likely to be much higher). The other problem Robinhood had was that they couldn't predict retail demand, or subsequent behavior, because there isn't any history to backtest.

Robinhood could be reasonably confident that a traditional IPO would lead to a pop, and the pop would consist of their customers buying, which would mean a) getting a bad price, and more importantly b) getting a worse price than institutions. Whereas selling to them directly at least meant that everyone got the same deal; if Robinhood shareholders lost, they lost in the same proportion as institutional investors. The Robinhood S-1 talks a lot about democratizing finance, and everyone losing money at the same time is certainly an example of that.

Convergence

The Economist highlights the fact that emerging market convergence happened faster than expected in the early 2000s, but has slowed down since then ($). One reason for the surprisingly rapid growth was that China grew faster, for longer, than observers expected. The acronym BRICs was coined in 2001 to refer to the biggest emerging markets—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—but in practical terms it's better to think of them as the briCs, with China's demand for raw materials fueling growth in other countries. China's scale meant that the country could get overwhelmingly large in manufacturing, and only slowly lose it to other countries; since intra-China inequality is still high, there's a labor arbitrage within China that makes offshoring low-margin industries less pressing. Another issue that was less obvious when the emerging market bull thesis was articulated in the early 2000s, but is more apparent now, is how much more state capacity and government stability matter when supply chains are complicated. Cheaper shipping means different countries can specialize in different goods, but it also means that civil disorder or conflict in any link in the supply chain can break it entirely.

Underinvestment

Cyclical industries get cyclical when supply responds to demand on a long lag. Even if aggregate demand is following a fairly steady long-term trajectory, there can be supply gluts or shortages if production doesn't line up with consumption. This may be happening in energy, where capital expenditures for S&P 500 companies have dropped by around three quarters, and are now only 44% of depreciation expenses. This, to be clear, is what shareholders have asked for: the big capex projects haven't led to great returns, and the long-term demand outlook is for a peak during the useful life of assets being purchased now, rather than at some point in the indefinite future. US energy companies were scarred for years after the $1.5 billion dry hole in Mukluk, Alaska, in 1984; domestic oil production dropped in 22 of the next 24 years, before growing again once fracking started working. Industries can go through very long cycles where every executive is selected based on their ability to survive a tough market, and that selects for cautious spending and generous returns to shareholders. But even if demand does peak, a premature peak in supply can lead to higher prices.

Consumer-Friendly Defaults

One of the important background facts about credit is that not everyone manages to pay their debts. There are various ways to deal with this, with attendant costs and consequences, and as a general rule when countries get richer they get a little bit more willing to cut borrowers some slack. This makes sense, in two ways: first, in a poor country the misallocation of scarce resources is a bigger social problem; bad borrowers are either consuming things they didn't work for, which makes the country poorer, or they're allocating resources to bad projects, which keeps the country poor. But also, richer economies tend to grow fastest with steady expansion of credit, which supports demand—I've previously referred to money in its various forms as minted certainty, and richer countries have more certainty to go around. So it's an interesting development that Shenzhen is allowing borrowers to declare personal bankruptcy to renegotiate their debts ($, Economist). It's difficult to read too much into local policy; the more local it is, the more experimental it is. But generally, allowing people to declare bankruptcy creates a better functioning system than the alternative, so this could easily spread, which would accelerate China's transition to a more consumption-driven economy.

The Amazon Rollup Boom

Extravagant efforts to attract customers tend to be a good peak-of-cycle indicator. Oracle's very tough run in the early 90s, when their stock lost 80% of its value in half a year, coincided with a sales campaign in which top salespeople were paid partly in gold. Salesforce spent almost 5% of their Series C funding on a single party for New Years Eve in 2000, after which the Nasdaq crashed and most of their customers went bankrupt. And now one company buying up Amazon sellers is offering a Tesla as a finder's fee ($, FT). I've written about this industry before ($), and it makes sense from a financial engineering perspective; from talking to Amazon sellers it seems to make less sense from an operating perspective. One possibility is that the rollup companies are trying to scale fast, and make scaling through acquisitions part of their story, so they're big enough to go public before growth slows down. (Amazon itself reported disappointing retail sales growth yesterday, and guided to slow growth in Q3, so if that's the plan they may have to act fast.)

Disclosure: I own shares of AMZN.

More from Hamming:

Another trait, it took me a while to notice. I noticed the following facts about people who work with the door open or the door closed. I notice that if you have the door to your office closed, you get more work done today and tomorrow, and you are more productive than most. But 10 years later somehow you don't know quite know what problems are worth working on; all the hard work you do is sort of tangential in importance. He who works with the door open gets all kinds of interruptions, but he also occasionally gets clues as to what the world is and what might be important. Now I cannot prove the cause and effect sequence because you might say, "The closed door is symbolic of a closed mind." I don't know. But I can say there is a pretty good correlation between those who work with the doors open and those who ultimately do important things, although people who work with doors closed often work harder. Somehow they seem to work on slightly the wrong thing - not much, but enough that they miss fame.

This is also true for investors. There's value in diving deeper into an intellectual rabbit hole than anyone else ever has, but feedback from smart peers has a great return in time-not-wasted; it's often easy to miss a single important flaw in a thesis you've been working on for a while, but an outsider will spot it right away. ↩

For quant funds, the One Big Thing might be finding a systematic way to recruit smart people. There are very large performance gaps between the excellent and the merely very good. ↩

I plan to write about this in more detail soon, and would be delighted if any readers who have strong opinions on the goal of QE and TIPS buying could chime in and share them with me. So far, everyone I've talked to sees this as mysterious, and I do, too. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart