I’m doing a Callin show later today on contrasting the last cleantech boom with the current one.

BuzzFeed and the Platform Squeeze

Michael Porter's five forces framework, like many academic theories, is both superficially obvious and a good checklist for not making obvious mistakes. It's clear that some companies are able to acquire new customers and raise their prices pretty easily, while others are stuck paying market price for inputs, accepting market price for outputs, and, if they're lucky, earning a market return on their assets. And there are only so many ways this can come about.

Media companies tend to go through shifts where they're relatively weak, and times when they're quite strong. The most effective way to deliver a specific piece of content to the people who want to see it—and will either tolerate ads or pay for subscriptions to do so—changes all the time. Content can be artificially cheap when there's a ready supply of user-generated material, or when there's a new distribution option that is underappreciated by the incumbents.

At other times, distribution gets artificially expensive: when social networks were a bigger growth business, they wanted to promote news content and video because it led to more active users. As user growth slowed, and as Facebook and Twitter became synonymous with arguing about politics, the same sites tried to deemphasize controversial content—and news is more interesting when it's controversial—in favor of more anodyne and more lucrative fare. On the supplier side, there are lots of people willing to create memes for free, and most of them don't try to take legal action when those memes find their way onto sites with ads.

BuzzFeed, founded in 2006, has lived through several of these media cycles. The company was early to the business of finding and exploiting viral content, at a time when virality usually meant blog posts, email forwards, and instant messages (one of their first products, BuzzBot, sent links to trending topics over instant messages). The company started out as a product business, but realized that the way to scale their product was to throw people at it: there wasn't much money in purely distributing links to free content, but there was money in writing up buzzy stories and putting ads on them. Since it was born as an algorithm and later evolved into a company, BuzzFeed has always had a more rigorous, metrics-driven approach than the average news provider, which has sometimes rebounded in very favorable ways: the company didn't like the slow page loads caused by display ads, and chose to do sponsored content instead, which a) meant they weren't offering a completely commoditized product that could be easily compared with other companies, and b) made advertisers more locked in, since they were relying on BuzzFeed for both inventory and creative.

Purely algorithmic sites can be gamed (although in the cases of Google this turned into a competitive advantage: a search engine using the same ranking factors, but weaker anti-spam ones, can end up dominated by spammers who are trying and failing to game Google. So competitors have to do something very different). A purely editorial process can be gamed, too. An algorithmic system with humans in the loop is relatively robust, and can automate the grunt work without turning itself into an easily reverse-engineered state machine.

The company's glory days were in the early 2010s, when there was an easy content arbitrage: find popular threads on Reddit, convert them into listicles, and get the listicles popular on Facebook and Twitter. (You can see an example of this here on BuzzFeed and here on Reddit, though the BuzzFeed article is somewhat surreal since it's a gallery of images and every single one has been taken down. True to the site's virality-above-all-else ethos, all eighty blank images have social sharing buttons.) At one level this is not especially useful to the world, although in a sense it serves the same purpose as a literary agent or record label: get good at finding where the obscure-but-interesting stuff is, and share the best of it with the wider public.

But, per the Porter's analysis, this creates a problem: it's constantly sending traffic from one aggregator, BuzzFeed, to another, Reddit. And which one users stick with is not a fixed quantity. Over time, purely user-generated sites get more content out of inbound users than editorial ones, so if one leg of the arbitrage involves sending traffic to a competitor, it also means sending traffic to a competitor who is constantly improving. The same thing can happen in the other direction: a less engaging news site doesn't want to share traffic with BuzzFeed, because it's likely to lose users to it. And there are problems on the editorial side, too. The number of people who want to write for a living exceeds the number of good livings to be had writing for large publications. But writers can go directly to their audiences, which means they're less afraid of losing their jobs. And writers who focus on news have a good sense of when in the news cycle labor action will make the biggest impact, so BuzzFeed New's unionized workers are staging a walkout the day BuzzFeed SPAC merger is finalized.1

The company is not a pure aggregator of content, of course. Those striking workers are part of the BuzzFeed News operation, which does original reporting and has won a Pulitzer. It's a legitimate news organization: The litmus test for this is that they are able to do stories whose content would get an individual banned from Twitter.2

Right now, it's hard to say where in the stack BuzzFeed sits in the ecosystem. In the last quarter, they got 55.8% of their revenue from traditional banner and video advertising, 29.4% from sponsored content and content licensing, and 14.8% from commerce. So the company has some elements of a pure media company, some of an ad agency, and some of a lightweight e-commerce player.

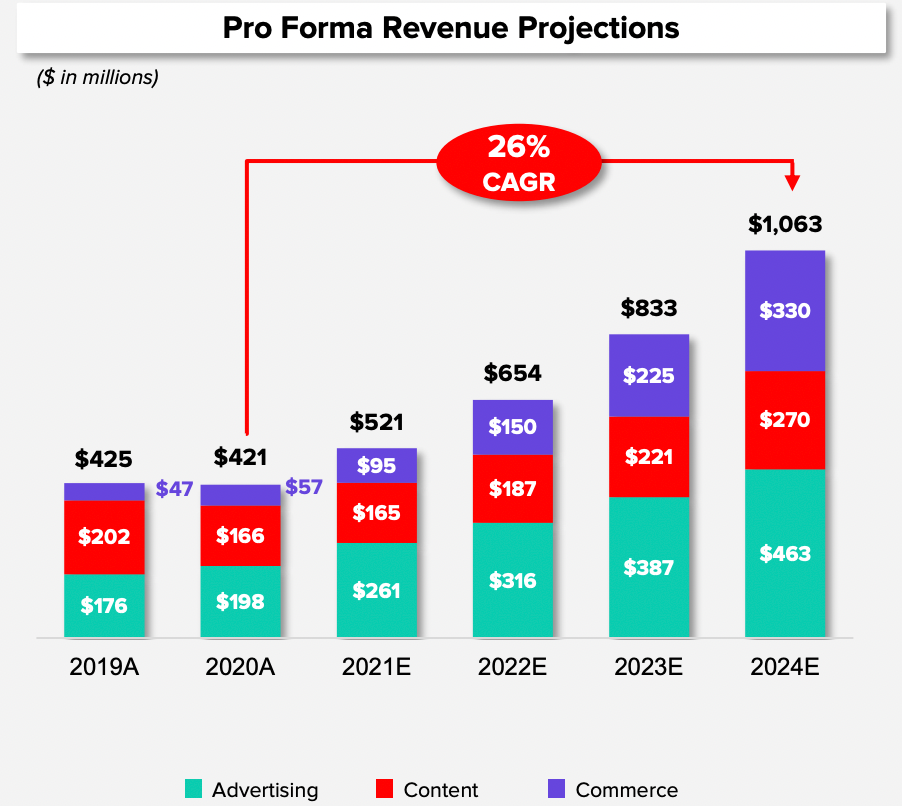

It's possible for all of these to work together nicely: selling banner ads and sponsored content means that BuzzFeed can titrate up the monetization over time. In their investor deck, BuzzFeed highlights the potential of their commerce business, which was 14% of 2020 revenue and is expected to be 40% of their growth through 2024. Commerce moves them lower in the stack, and helps set a sort of reserve price for their other monetization outlets: if advertisers aren't paying enough for space, and if content partners aren't interested in the content BuzzFeed likes, the company can just use that inventory to sell things directly.

But this model means that BuzzFeed is very complicated for a ~$500m business: it's competing fiercely for attention, has limited control over its supply of readers and its supply of stories, and has to make difficult tradeoffs between various revenue models whose payoffs may take time, or be uncertain. This kind of dynamic is fine for a larger business, but tricky for a smaller one. And BuzzFeed does want to be bigger: they acquired Complex Networks, a smaller competitor with a similar model (albeit less of a content focus), and Jonah Peretti, their CEO, has called for other media sites like Group Nine, Vox, and Refinery29 to merge.

The Information says BuzzFeed competitor Bustle is having trouble closing a SPAC deal before there's more clarity on how BuzzFeed itself performs. But BuzzFeed's SPAC deal is getting a large number of redemptions ($, WSJ), which augurs poorly for it over time (not just because it's a negative vote from investors but because the PIPE financing for the transaction costs BuzzFeed 8.5% rather than 7% if there are too many withdrawals).

If BuzzFeed's public debut is disappointing, and other online media companies have trouble either raising more funding or going public, it would be an interesting vindication for Peretti's thesis: they really will need to consolidate or die, and BuzzFeed, as the one publicly traded stock as currency, could end up doing the consolidating. The paradox of the BuzzFeed offering is that the best thing for the company strategically is the worst for it tactically: disappointing growth, a low valuation, and the opportunity to be the buyer of last resort in an industry that—as BuzzFeed’s management correctly deduced—needs to consolidate to survive.

Further reading: Jacob at A Media Operator has written some good pieces on BuzzFeed, specifically here and here.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Here's a dirty secret: part of equity research consists of being one of the world's best-paid data-entry professionals. It's a pain—and a rite of passage—to build a financial model by painstakingly transcribing information from 10-Qs, 10-Ks, presentations, and transcripts. Or, at least, it was: Daloopa uses machine learning and human validation to automatically parse financial statements and other disclosures, creating a continuously-updated, detailed, and accurate model.

If you've ever fired up Excel at 8pm and realized you'll be doing ctrl-c alt-tab alt-e-es-v until well past midnight, you owe it to yourself to check this out.

Elsewhere

The Great Unclogging

Container prices from Southeast Asia to the West Coast are down 25% from November, although still up 279% from last year. Container prices are always volatile, as a look at the long-term chart of the Baltic Dry Index shows. And they're a sort of second-order indicator: they represent not just the demand for goods but how much shippers worry about future supply constraints. So extreme changes happen, but the directional view is meaningful: shipping is still incredibly expensive, but for the moment it's getting cheaper.

The First-Party Data Gold Rush

As third-party tracking gets more deprecated, retailers are looking for better ways to collect first-party data ($, WSJ). What looked like a sea change in privacy norms turns out to be a radical shift in who does the tracking and how lucrative it is. Platforms that monetize through ads get scale benefits, but they don't capture the maximum possible upside unless the ad market is extremely competitive. The more heterogeneous the data—the more distinctively individual consumers behave—the more upside accrues to retailers instead of the companies they advertise with. Cookie deprecation and Covid happened at roughly the same time coincidentally, but each one has raised retailers' returns on data, a benefit that will skew to the largest retailers.

Open Data

A new Colorado rule requiring companies to post salary ranges has created a large salary database for jobs in the state ($, WSJ), including roles at some large companies. One of the forces that keeps wages somewhat low is a lack of salary transparency: it's hard to negotiate against someone who has a better sense of their own negotiating position. Especially for people who have a hard time getting an offer in the first place, soliciting enough bids for their work to know what the real market price is can be effectively impossible. And while some of these jobs are local, many of them—from software engineers to customer service reps—can be done from home, so Colorado is effectively forcing nationwide transparency in base pay for certain jobs.

Bitcoin Loans

Goldman Sachs is looking into providing loans against Bitcoin holdings. Part of the standard "Buy, Borrow, Die" formula is to avoid realizing capital gains by borrowing against appreciated assets, and for some crypto holders, their cost basis is essentially zero. Among these people are some Bitcoin maximalists who a) feel morally opposed to ever selling a single Satoshi, but b) wouldn't be opposed to enjoying their newfound wealth. A lender against crypto either wants to demand extreme overcollateralization or wants to hedge their exposure to the underlying asset, and a fun wrinkle to this trade is that Bitcoin futures are in contango, so someone with a business reason to be short Bitcoin can pick up some extra return from doing so.

The Arms Race

Trae Stephens has an unapologetic piece on the US/China arms race. The US certainly spends a lot on weapons, but seems to be getting a dwindling bang for escalating bucks. There aren't stable equilibria in international relationsL someone always wants more, or worries that someone else does.

Diff Jobs

As a reminder, Diff Jobs is our recruiting service that connects Diff readers to companies looking to hire them. There is no cost to employees. Some new and active roles we're looking for:

- A crypto platform is looking for a Head of Security Research to support their portfolio companies. It'll be a great role for someone who combines a STEM research background with software engineering and crypto interest. (remote)

- Software Engineers (front-end, back-end). The market for engineers is red hot right now, and we're working with a number of interesting startups (seed to series B) looking for readers of The Diff to join their company. Please tell us your programming languages in the form so we can quickly find what might be a fit. (various locations)

- A B2B sales leader who is looking join a Series B FinTech, which is helping small businesses build financial relationships that accelerate their growth. (SF)

- Consumer Product Managers, in eCommerce or EdTech, (UK-based) FinTech. (various locations)

- We're looking to fill quite a few data science roles, one of which is a marketing data scientist for a company democratizing financial access across emerging markets. (NYC, remote)

On the employer side: we are especially interested in talking to companies looking for more senior people on the product side. We'd also like to talk to firms on the buy-side in equities and credit; as the traditional start-of-year game of musical chairs commences, we'd love to work with you.

There is something truly beautiful about employees of a company that's good at search engine optimization setting up their strike so it will rank well on searches for "BuzzFeed SPAC" and related terms the day those searches peak. ↩

This is not necessarily a huge social problem or anything. There are just different norms for different professions. If you spent a couple weeks asking strangers or distant acquaintances for gossip about someone, that would be seen as weird and stalker-like behavior, but that's necessary to produce an article like this piece or this one ($, Business Insider). A rule against sharing hacked documents will reduce foreign election interference, but would also have prevented Snowden's leaks or the Pentagon Papers. And good finance journalism often means inducing people to leak material nonpublic information in violation of a duty to keep it confidential, in exchange for personal gain (in the form of getting a scoop).

It's a bit analogous to the fact that banks can create money but you can't personally counterfeit bills—some activities are socially useful but dangerous when widespread, and either norms or regulations restrict who can do them. In a US context, strong free speech protections mean that the means is social rather than legal, although as the connotation of "social" switched from "social norm" to "social network," we've ended up in a situation where the limits of speech are implemented in a more legalistic way. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart