The Network Before the Internet

A stylized history of the Internet might go like this: decades ago, deep in the military-industrial complex, there were concerns that the US needed more resiliency in the face of nuclear war. Meanwhile, computing experts felt that high-quality connections between central nodes could be valuable in its own right, which they found a far more compelling argument. This project wouldn't have happened without government subsidies—without the confluence of military interest and technocratic management. But soon after this initial boost, most of its benefits (and most of its usage) were pushed by private interests, rather than public ones. The project was a subsidized substrate for a wild free-market experience, creating immense growth and ensuring that when most normal people interacted with the network, they were mostly interacting with for-profit companies rather than thinking about a government program.

But this story also happened half a century earlier, with the interstate highway system. It featured some of the same driving forces—simmering technocratic desire to build a big, standardized system; Cold War paranoia about the risk of slow mobilization of US forces; a big bet that building a new network would induce demand. Both even featured cameo appearances by Senator Al Gore (albeit different Gores, thirty years apart).

The highway system, like the Internet, started out without a direct commercial imperative: it was clearly valuable, but it was built to let private citizens travel, not to enable new business models. The system's prehistory starts with the dire state of American roads in the early twentieth century. In 1919, the US military decided to test out the country's roads by sending a convoy of 72 vehicles from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. Their average speed while driving worked out to under 6 miles per hour, compared to a planned 15. Part of the problem was that most roads in the US were poor quality, and bridges were generally designed with horses or small cars in mind, not heavy trucks. (The convoy ended up destroying several dozen bridges.)

A series of laws tried to remedy this situation, including one offering federal matching funds for state road construction in 1916, another larger one in 1921, and a plan for a national highway system in 1938. Wars disrupted the first and last of these, but in the postwar period roadbuilding was a particularly attractive area for government spending both because of the US's experience with Germany's infrastructure and because of the potential for high unemployment as the military demobilized.

Aside from the general increase in the ease and speed of transportation, and the increase in sales for cars and especially trucks, the highway system spawned a number of successful companies:

- McDonald's grew from 4 locations in 1954 to 500 in 1964.

- Holiday Inn started franchising in 1957, and had fifty locations in 1958 and a thousand ten years later.

- Howard Johnson's got an earlier start on the East Coast, and focused on serving long-distance travelers there with a standardized offering and strategic locations along high-traffic roads.

They didn't just restructure demand, but also changed supply. Consider the retail business: trains are better for bulk transportation than trucks, but have a limited service area and timing. So the way retail works in a train-centric world is that there are large stores with diverse products in big cities, and smaller ones with a more limited selection, much more expensive products, and inconsistent inventory in more rural areas. But trucks allow retail to work well even in fairly remote places, and since truck transportation costs are a function of distance and time without high capital costs, the economics look pretty similar from one small town to the next. So the interstate highway system can also treat Walmart as one of its progeny.1

These companies ended up with decent representation in the 1970s-era "Nifty Fifty"—the large, stable growth stocks that kept performing when the 60s boom in small growth companies and conglomerates fell apart.

The project didn't just reshape big companies, though; it also changed cities. Highways made suburbs more viable, both because they sped up commutes from outside big cities and because they disrupted communities within them.2

One feature of big platforms is that scaling on the platform happens faster than the scaling of the platform. Depending on how you count, the highway system took a generation or two to build, but also allowed some companies to go from startups to ubiquitous in just a few years. The same dynamic applies to more modern platforms: a TikTok star's growth curve is more hockey-stick than TikTok's, Zynga grew faster than Facebook by using Facebook's ads and social tools effectively, Compaq set growth records that Microsoft and Intel couldn't match by effectively contributing to their duopoly, and companies that figure out their unit economics with search ads can ride a very steep S-curve.

But what sets the Internet and the Interstate Highway System apart from these platforms is that it didn't have a profit-seeking owner. Building on a platform means ceding control to that platform, and that runs two risks:

If the business creates a negative externality for other platform users, it risks getting shut down, and

If it creates a consumer surplus and turns a profit, the platform has an incentive to incorporate its features—the profits are attractive, and that consumer surplus makes the rest of the platform more valuable, so it's nearly always optimal to absorb or supplant something built on a platform.3

A public or nonprofit-owned platform still cares about the first concern, and will try to route around it, but it doesn't really care about the second. Especially because the benefits are so diffuse, there isn't much political will to claw back Walmart's profits from cheaper trucking. (In fact, the highway system sometimes gets criticized as a giveaway to car companies, but that's a weaker claim: car sales tracked well ahead of road improvements for decades, and high-quality roads mean that cars don't have to be replaced as often.)

These platforms are rare, but there are more than two examples. A few other cases that look a lot like successful non-profit platforms that lead to private-sector opportunities include:

- Effective public education, which has the first-order effect of creating a literate population and the second-order effect of doing much finer-grained filtering to connect people to the jobs where they'll be the most valuable.

- 19th century railroad booms in the US and UK had major government subsidies (in the US case they were direct; in the UK case, the indirect subsidy came from the government's limitations on company formation; the railroads that were allowed to form got preferential access to both routes and private capital).

- The joint-stock corporation itself is provided by governments as a public good (limited liability doesn't work without some kind of backstop), but mostly creates private value. Free-trade zones also have this function—the EU's common market has helped peripheral countries join up with bigger economies' more established supply chains, and the US and Mexico have had similar convergence.

- Programming languages and libraries are a mostly privately-organized version of this; with a handful of exceptions, the popular ones are free to use, but the value created with them is mostly within for-profit companies.

- One that's happening right now is India's Unified Payments Interface, which has made the Indian financial system much more interoperable and helped separate the user experience of financial services from the balance sheets required to provide them.

Privately-held platforms get a lot of justifiable love from investors. What could be better than building the most abstract part of the business and then collecting a royalty on all the object-level efforts that make it work for specific users? But there's plenty of upside in building on platforms, too, especially when those platforms don't have a P&L.

Further reading: The Big Roads has much more detail on the conception and construction of the interstates.

A Word From Our Sponsors

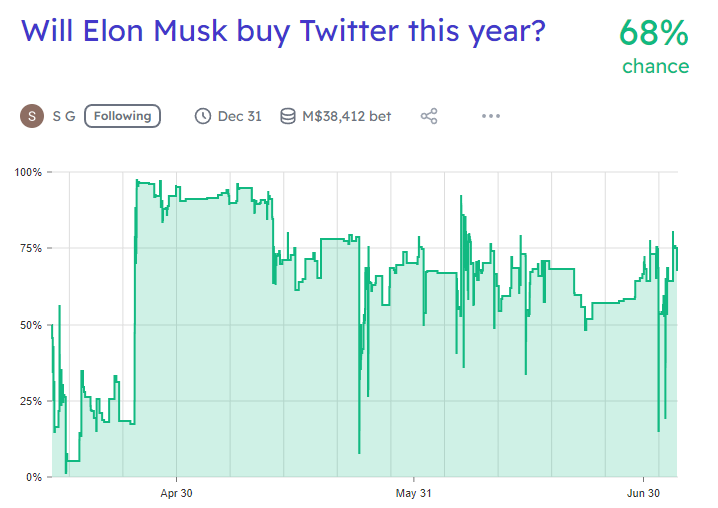

Manifold Markets is a play-money prediction market for betting on just about anything, from when specific new technologies will be available to questions about specific people. Prediction markets are a powerful tool for aggregating collective wisdom, but they're also a fun tool for speculating about the future, learning what other people think, and arguing with them.

The site uses a play currency, Mana, which can be cashed out to donate to charities, or which can be retained in the site as a way to keep score and earn bragging rights.

Elsewhere

Operational Issues

The usual way to look at capacity constraints is that companies don't like to buy long-lived fixed assets like oil refineries, ships, or planes unless they're sure that there will be long-term demand that justifies them. But another piece of this is the constraint on institutional knowledge: when business is bad, companies downsize or accept attrition, and that means they lose some of the expertise that allows them to operate at full capacity. Airlines are seeing this now; an American Airlines scheduling glitch allowed pilots and copilots of up to 12,000 flights to cancel flying plans ($, WSJ), and now the pilots' union is asking for a 200% pay bump to bring them back. This is not limited to US companies; in the UK, EasyJet's COO has resigned after a spate of mass flight cancellations.

This kind of issue has cropped up frequently during the economic recovery. Even though employment is recovering, the increase in turnover means that workers will initially be less productive (though it's possible that they'll end up being more productive than they otherwise would be (at least, that's what one long-term study in a developed country shows, although in the short-term the disruption is negative). For businesses that need to deliver goods or people to specific places, this shows up in delays and cancellations, but the less measurable effect is on the availability and quality of services. If service businesses are less productive because more experienced employees have moved around, high demand can mean that they're still doing as much business as before, just with lower quality and less availability.

The Cloud

FedEx plans to retire its mainframes and close its datacenters by 2024, with planned savings of $400m. This is a good reminder that despite a decade of strong growth, cloud penetration still has a ways to go. Amazon says only 10% of IT spending has moved over, for example, though they're naturally biased.

One way to think about this is that adopting new technologies is easier if there isn't a legacy option to displace them; cloud computing was a very easy decision for companies that didn't have an existing investment in another model, and the longer they'd been operating with mainframes, the riskier and more difficult the switch would be. The upside to this is that the hardest-to-win contracts are also sizable, and since the challenge of switching is a combination of technical issues and institutional ones, they're also customers who will tend to stick around.

Disclosure: Long AMZN.

Rent and Inflation

When a metric starts to matter more, it's important to dive in and understand how it's calculated and what drives it. Figuring out inflation rates is nontrivial. (Consider college during lockdowns: if the price doesn't change but the venue switches from a nice campus to a Zoom window, clearly either college has gone down in quality or the price of Zoom lectures has gone way up, but inflation measures aren't agile enough to pick up on this.) An important pair of stylized facts about the CPI is:

- The cost of shelter is the biggest single component of CPI, and

- This is calculated by asking people about current rents, so at times when rents are changing rapidly, it's a lagging indicator; a two-year lease signed in the summer of 2020 will be much cheaper than current market rates just about everywhere, but won't show up that way in the CPI.

So it's useful to look at asking rent trends on Zillow as a preview of what headline inflation will look like in the coming months. Rents are no longer accelerating, but aren't dropping much, either. The good news is that central banks spend a lot of time debating the finer points of these kinds of measurements, and are not oblivious to their limitations.

The Glut

The WSJ has a good piece on how the inventory liquidation business is booming ($) as large retailers get rid of their excess inventory. There's a whole ecosystem for dealing with inventory that's been over-ordered; one reason the dollar store industry has prospered so much in the last few decades is that larger retailers are so inventory-averse, so there's an ample supply of marked-down inventory, albeit a fairly random sampling.

One way to look at those companies is that they're partly an expected-returns arbitrage. Holding Christmas decorations in a warehouse from July through November is anathema to a company that obsesses over its inventory turnover ratio, but to a business that cares about gross margin (and has a warehouse footprint geared towards cheap long-term storage instead of high turnover) this can be a fair trade. In fact, you can look at the discount versus full price ecosystem as partly a way to move inventory to whichever balance sheet is willing to hold it—ideally consumers, briefly large chains, and, as a last resort, deep discount sellers.

Credit and Macro

This piece is a good meditation on how hard it is to incorporate credit quality into macroeconomic models. One of the problems is the Minksy argument: more credit availability makes loans look better, and that leads to more credit until the low quality of the loans is undeniable, at which point the whole process reverses. This is clearly a big cyclical driver, at least some of the time (there's a reason the vogue for Minsky really kicked off in 2007, though his views applied well to levered-up fiber-optics companies in the late 90s, too). One of the difficulties with agent-based modeling in general is that to be realistic, the agents have to do dumb things, but they also have to do dumb things in clever ways. It's computationally expensive to model this process, and even a very sophisticated model won't capture all of the financial sector's creativity.

Diff Jobs

Diff Jobs is our service matching readers to job opportunities in the Diff network. We work with a range of companies, mostly venture-funded, with an emphasis on software and fintech but with breadth beyond that.

If you're interested in pursuing a role, please reach out—if there's a potential match, we start with an introductory call to see if we have a good fit, and then a more in-depth discussion of what you've worked on. (Depending on the role, this can focus on work or side projects.) Diff Jobs is free for job applicants. Some of our current open roles:

- The Diff is looking for an associate to support Diff Jobs, newsletter growth, research, and other areas of the business. (Remote, Austin a plus)

- A startup that helps companies' financial systems seamlessly communicate is looking for a mid/senior-level engineer, C#/.NET experience ideal. (Austin)

- A startup helping prevent financial crime in the crypto ecosystem is looking for software engineers across a variety of roles: backend, ML, and dev ops. (US, remote)

- A company building financial services for small businesses is looking for a senior engineering leader. (SF)

- An alt data consultancy is looking for a data scientist to join their team. (US, remote)

Because Walmart came of age at a time of high nominal interest rates and high inflation, it benefited more than it otherwise would have from supply chain management and tight controls on inventory. Managing this is uniquely achievable with trucks, where it wasn’t previously possible with trains before precision scheduled railroading (see this post for more on railroads). ↩

Even when roads ultimately didn't pass through some neighborhoods, extended debates over where they should go were toxic for property values: when people thought their houses would be demolished soon, they didn't have an incentive to maintain them, and people with the means to do so left early. This was not the only contributor to cities' mid-century death spirals, but certainly had an impact—especially because suburbs allowed commuters to live far outside town, commute to a fairly safe downtown, and remain hermetically sealed from the rest of the city.

A good lesson from this is that transformative technologies have winners and losers, and that the best way to address this is to swiftly identify and compensate the losers (if they’re going to be compensated at all). Policy can turn a painful disruptive period into a Pareto improvement, but only if it’s well-calibrated. ↩

This is not always true, of course. Two forces that push against it are 1) when there's a long tail of valuable businesses, such that no one of them would make a big difference and copying all of them would be a chore, and the closely related 2) when the platform owner believes that they're early in the discovery process of what the platform is for, and don't want to capture the best current use at the cost of missing the 10 even-better-uses that haven't been developed just yet. Notably, the power of point 2 depends in part on assumptions about platform economics, but also on discount rates: when a platform owner feels economically secure, and real interest rates are low, it's optimal to wait a long time to maximize opportunities rather than hurrying to take advantage of the ones that have already presented themselves. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart